I always find Dr. Moffic’s articles in Psychiatric Times thought-provoking and his latest essay, “Enhancement Psychiatry” is fascinating, especially the part about Artificial Intelligence (AI). I liked the link to the video of Dr. John Luo’s take on AI in psychiatry. That was fascinating.

I have my own concerns about AI and dabbled with “talking” to it a couple of times. I still try to avoid it when I’m searching the web but it seems to creep in no matter how hard I try. I can’t unsee it now.

I think of AI enhancing psychiatry in terms of whether it can cut down on hassles like “pajama time” like taking our work home with us to finish clinic notes and the like. When AI is packaged as a scribe only, I’m a little more comfortable with that although I would get nervous if it listened to a conversation between me and a patient.

That’s because AI gets a lot of things wrong as a scribe. In that sense, it’s a lot like other software I’ve used as an aid to creating clinic notes. I made fun of it a couple of years ago in a blog post “The Dragon Breathes Fire Again.”

I get even more nervous when I read the news stories about AI making delusions and blithely blurting misinformation. It can lie, cheat, and hustle you although a lot of it is discovered in digital experimental environments called “sandboxes” which we hope can keep the mayhem contained.

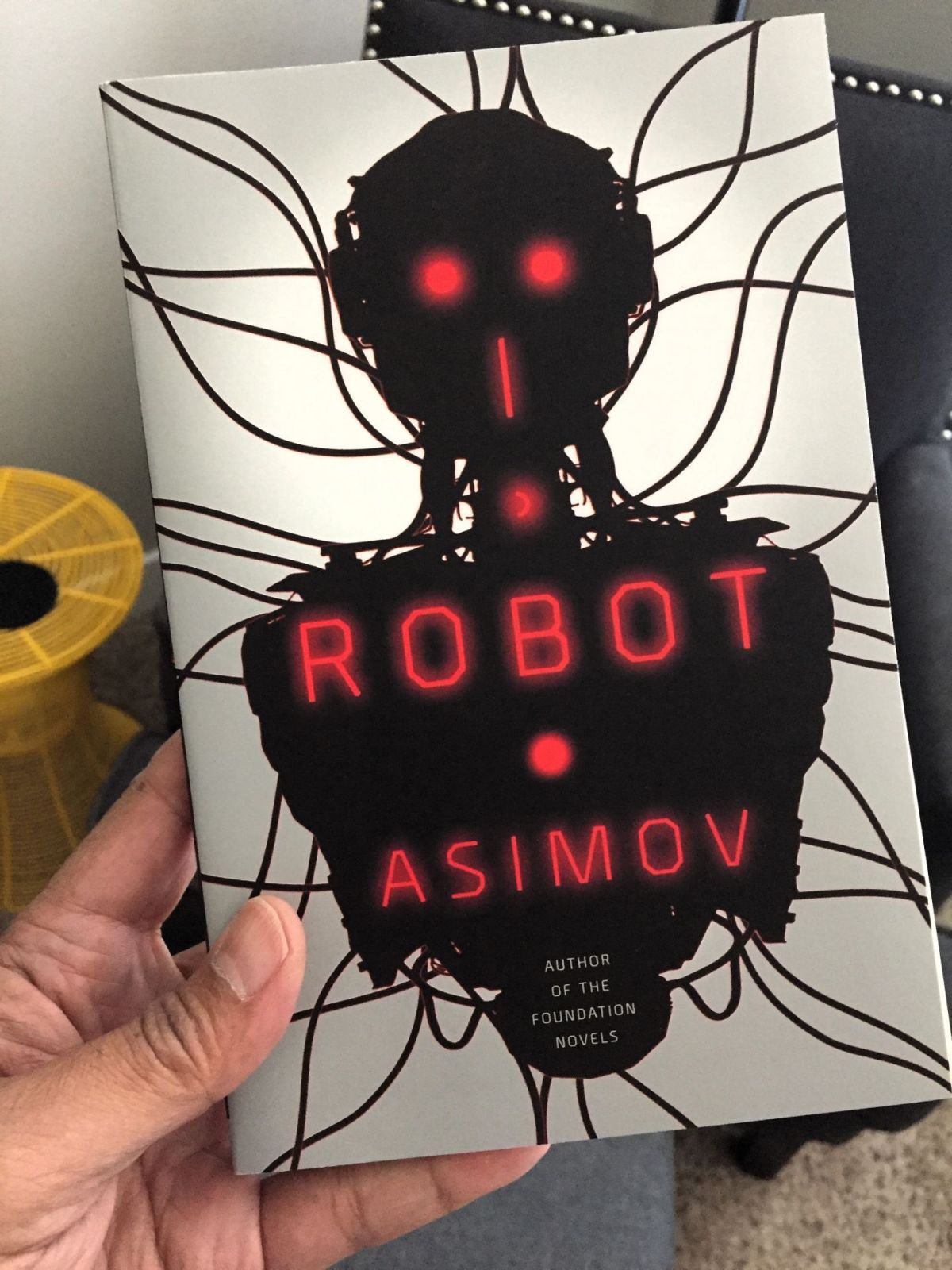

That made me very eager to learn a little more about Yoshua Bengio’s LawZero and his plan to create the AI Scientist to counter what seems to be a developing career criminal type of AI in the wild west of computer wizardry. The LawZero thing was an idea by Isaac Asimov who wrote the book, “I, Robot,” which inspired the film of the same title in 2004.

However, as I read it, I had an emotional reaction akin to suspicion. Bengio sounds almost too good to be true. A broader web search turned up a 2009 essay by a guy I’ve never heard of named Peter W. Singer. It’s titled “Isaac Asimov’s Laws of Robotics Are Wrong.” I tried to pin down who he is by searching the web and the AI helper was noticeably absent. I couldn’t find out much about him that explained the level of energy in what he wrote.

Singer’s essay was published on the Brookings Institution website and I couldn’t really tell what political side of the fence that organization is on—not that I’m planning to take sides. His aim was to debunk the Laws of Robotics and I got about the same feeling from his essay as I got from Bengio’s.

Maybe I need a little more education about this whole AI enhancement issue. I wonder whether Bengio and Singer could hold a public debate about it? Maybe they would need a kind of sandbox for the event?