I was looking at an early version of the handbook of consultation-liaison psychiatry that eventually evolved into what was actually published by Cambridge University Press. I wrote virtually all of the early version and it was mainly for trainees rotating through the consult service. The published book had many talented contributors. I and my department chair, Dr. Robert G. Robinson, co-edited the book.

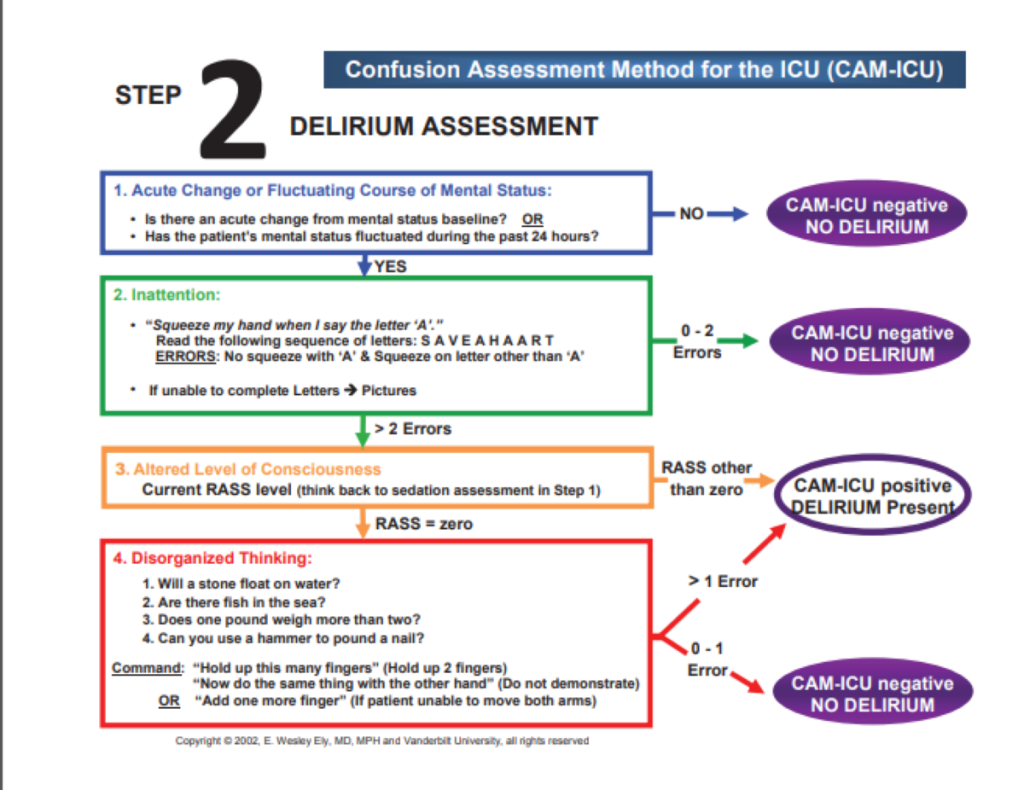

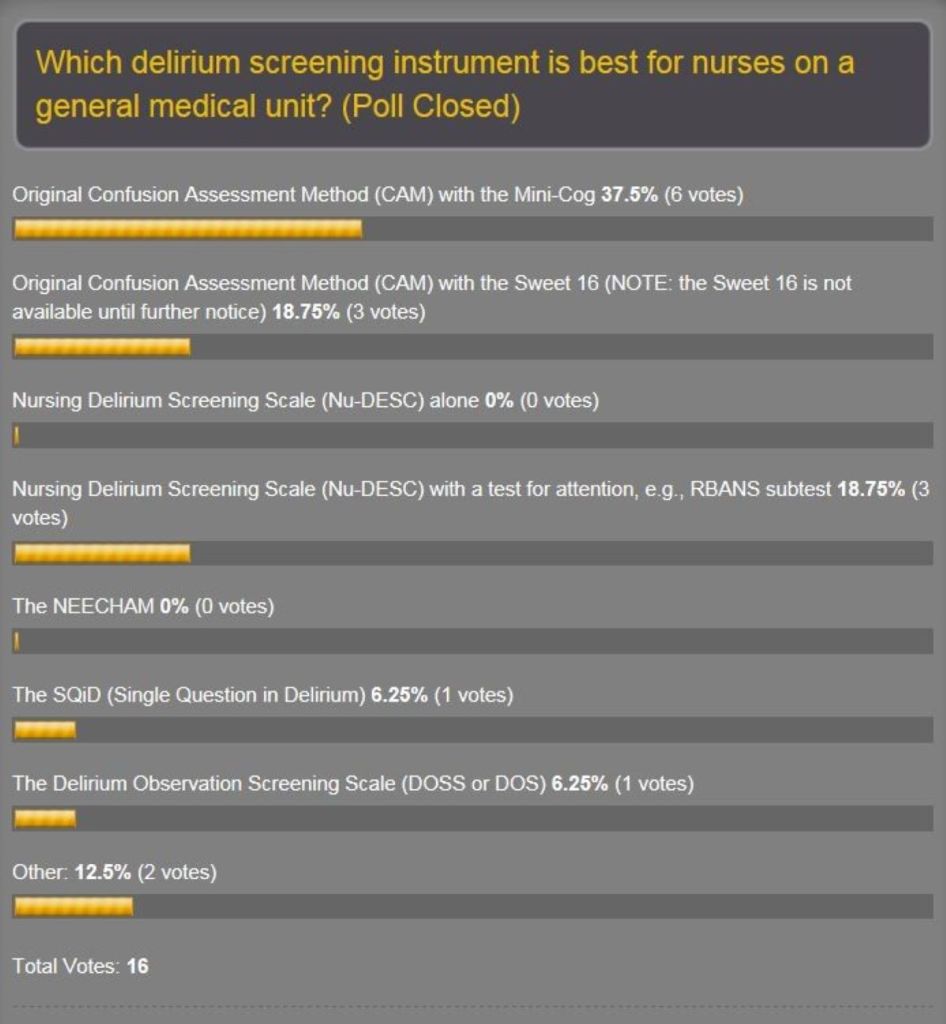

In the introduction I mention that the manual was designed for gunslingers and chess masters. The gunslingers are the general hospital psychiatric consultants who actually hiked all over the hospital putting out the psychiatric fires that are always smoldering or blazing. The main problems were delirium and neuropsychiatric syndromes that mimic primary psychiatric disorders.

The chess masters were those I admired who actually conducted research into the causes of neuropsychiatric disorders.

Admittedly the dichotomy was romanticized. I saw myself as a gunslinger, often shooting from the hip in an effort to manage confused and violent patients. Looking back on it, I probably seemed pretty unscientific.

But I can tell you that when I followed the recommendations of the scientists about how to reverse catatonia with benzodiazepines, I felt much more competent. After administering lorazepam intravenously to patients who were mute and immobile before the dose to answering questions and wondering why everyone was looking at them after the dose—it looked miraculous.

Later in my career, I usually thought the comparison to a firefighter was a better analogy.

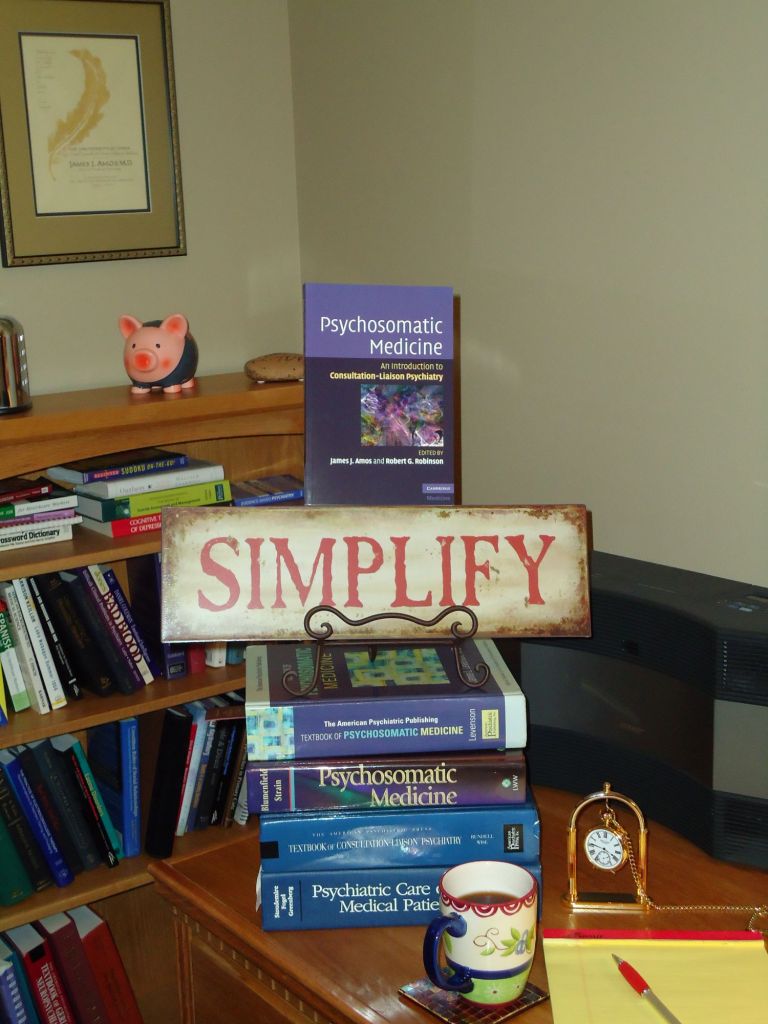

The 2008 working manual was called the Psychosomatic Medicine Handbook for Residents at the time. This was before the name of the specialty was changed back to Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry. I wrote all of it. I’m not sure about the origin of my comment about a Psychosomatic Medicine textbook weighing 7 pounds. It might relate to the picture of several heavy textbooks on which my book sits. I might have weighed one of them.The introduction is below (featured image picture credit pixydotorg):

“In 2003 the American Board of Medical Specialties approved the subspecialty status of Psychiatry now known as Psychosomatic Medicine. Long before that, the field was known as Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry. In 2005, the first certification examination was offered by the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. Both I and my co-editor, Dr. Robert G. Robinson, passed that examination along with many other examinees. This important point in the history of psychiatry began many decades ago, probably in the early 19th century, when the word “psychosomatic” was first used by Johann Christian Heinroth when discussing insomnia.

Psychosomatic Medicine began as the study of psychophysiology which in some quarters led to a reductionistic theory of psychogenic causation of disease. However, the evolution of a broader conceptualization of the discipline as the study of mind and body interactions in patients who are ill and the creation of effective treatments for them probably was a parallel development. This was called Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry and was considered the practical application of the principles and discoveries of Psychosomatic Medicine. Two major organizations grew up in the early and middle parts of the 20th century that seemed to formalize the distinction (and possibly the eventual separation) between the two ideas: the American Psychosomatic Society (APS) and the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine (APM). The name of the subspecialty finally approved in 2003 was the latter largely because of its historic roots in the origin of the interaction of mind and body paradigm.

The impression that the field was dichotomized into research and practical application was shared and lamented by many members of both organizations. At a symposium at the APM annual meeting in Tucson, AZ in 2006, it was remarked that practitioners of “…psychosomatic medicine may well be lost in thought while…C-L psychiatrists are lost in action.”

I think it is ironic how organizations that are both devoted to teaching physicians and patients how to think both/and instead of either/or about medical and psychiatric problems could have become so dichotomized themselves.

My motive for writing this book makes me think of a few quotations about psychiatry in general hospitals:

“Relegating this work entirely to specialists is futile for it is doubtful whether there will ever be a sufficient number of psychiatrists to respond to all the requests for consultations. There is, therefore, no alternative to educating other physicians in the elements of psychiatric methods.”

“All staff conferences in general hospitals should be attended by the psychiatrist so that there might be a mutual exchange of medical experience and frank discussion of those cases in which there are psychiatric problems.”

“The time should not be too long delayed when psychiatrists are required on all our medical and surgical wards and in all our general and surgical clinics.”

The first two quotes, however modern they might sound, are actually from 1929 in one of the first papers ever written about Consultation Psychiatry (now Psychosomatic Medicine), authored by George W. Henry, A.B., M.D. The third is from the mid-1930s by Helen Flanders Dunbar, M.D., in an article about the substantial role psychological factors play in the etiology and course of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and fractures in 600 patients. Although few hospital organizations actually practice what these physicians recommended, the recurring theme seems to be the need to improve outcomes and processes in health care by integrating medical and psychiatric delivery care systems. Further, Dr. Roger Kathol has written persuasively of the need for a sea change in the way our health care delivery and insurance systems operate so as to improve the quality of health care in this country so that it compares well with that of other nations (2).

This book is not a textbook. It is not a source for definitive, comprehensive lists of references about all the latest research. It is not a thousand pages long and does not weigh seven pounds. It is a modest contribution to the principle of both/and thinking about psyche and soma; consultants and researchers; — gunslingers and chess masters.

In this field there are chess masters and gunslingers. We need both. You need to be a gunslinger to react quickly and effectively on the wards and in the emergency room during crises. You also need to be a chess master after the smoke has cleared, to reflect on what you did, how you did it—and analyze why you did it and whether that was in accord with the best medical evidence.

This book is for the gunslinger who relies on the chess master. This book is also for the chess master—who needs to be a gunslinger.

“Strategy without tactics is the slowest route to victory. Tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat”—Sun Tzu.”

References:

1. Kathol, R.G., and Gatteau, S. 2007. Healing body and mind: a critical issue for health care reform. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. 190 pp.

2. Kornfeld, D., and Wharton, R. 2005. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychosomatic Medicine. Psychosomatics 46:95-103.