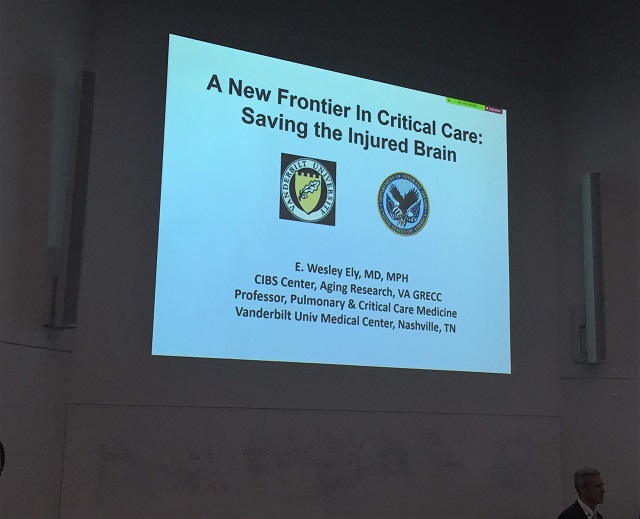

A few days ago, I read the news story about COVID-19 antivaxx vigilantes interfering with the medical care of patients hospitalized with COVID-19. The writer interviewed Dr. Wes Ely, MD, MPH. He’s an intensive care unit (ICU) specialist at Vanderbilt University.

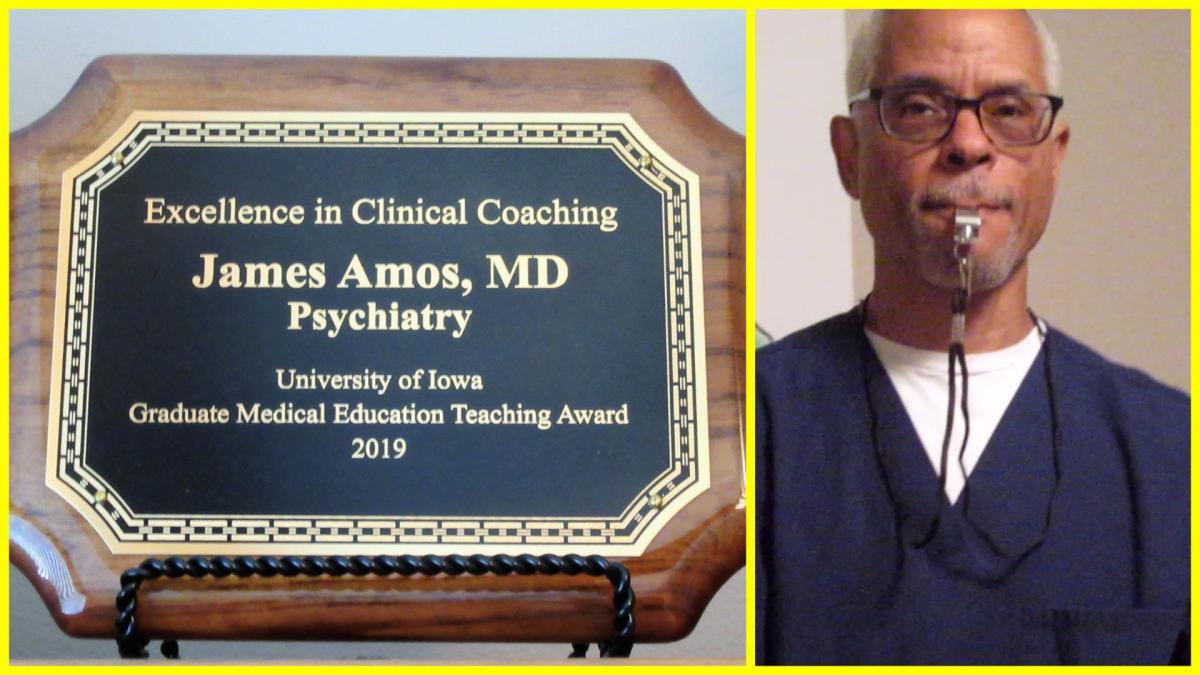

I first corresponded with Dr. Ely by email about 10 years ago when I wrote a blog called “The Practical Psychosomaticist.” I sort of poked fun of him in one of my posts about the chapter on psychiatrists and delirium in one of his books, Delirium in Critical Care, which he co-authored with another intensivist, Dr. Valerie Page, and published in 2011.

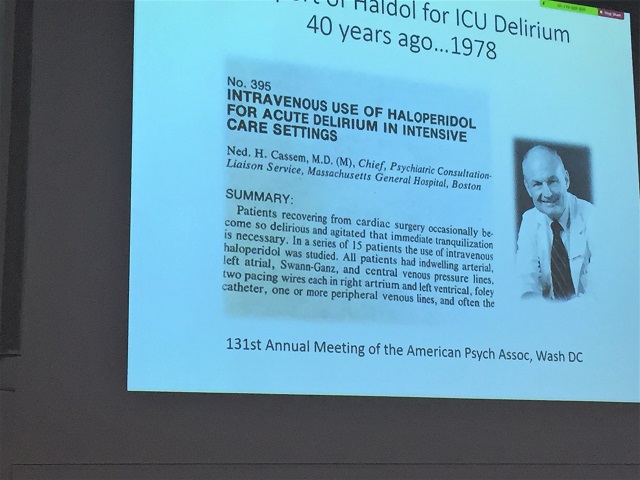

I can’t really tell the anecdote the way I usually told it to residents and medical students because of copyright rules but the antipsychotic drug haloperidol is mentioned. I made fun of the very short section “Psychiatrists and Delirium” in Chapter 9 (“Treatment of delirium in critical care”). It’s only a couple of paragraphs long and comically gives short shrift to the psychiatrist’s role in managing delirium. That’s ironic because I have always thought the general hospital psychiatric consultant’s role was very limited in that setting.

Maybe you should buy that book and, while you’re at it, buy the other one he recently published this month, Every Deep-Drawn Breath. My wife just ordered it on Amazon. It’s reasonably priced but in order to qualify for free shipping, she had to buy something else. It turned out to be Whift Toilet Scents Drops by LUXE Bidet, Lemon Peel (travel size, not that we’re traveling anywhere in this pandemic). Be sure to get the Lemon Peel.

In the email Dr. Ely sent to me and many others about the book, he said, “Every penny I receive through sales of this book is being donated into a fund created to help COVID and other ICU survivors and family members lead the fullest lives possible after critical illness. This isn’t purely a COVID book, but stories of COVID and Long COVID are woven throughout. I have also shared instances of social justice issues that pervade our medical system, issues that you and I encounter daily in caring for our community members who are most vulnerable.”

Anyway, the Anti-Vaxx vigilantes have played a big role in filling up the Vanderbilt ICU and many others by posting conspiracy theories about the COVID-19 vaccines on social media, which for some reason are hard to control. They persuade patients and their families that doctors are trying to kill them with the treatments that are safe and effective. Instead, they recommend ineffective and potentially harmful interventions such as Ivermectin, inhaling hydrogen peroxide, and gargling iodine.

There are different opinions about conspiracy theories and those who believe in them. Some psychiatrists say that conspiracy theories are not always delusional. One psychiatrist wrote a short piece in Current Psychiatry, Joseph Pierre, MD, “Conspiracy theory or delusion? 3 questions to tell them apart.” Current Psychiatry. 2021 September;20(9):44,60 | doi:10.12788/cp.0170:

What is the evidence for the belief? Can you find explanations for it or is it bizarre and idiosyncratic?

Is the belief self-referential? In other words, is it all about the believer?

Is there overlap? There can be elements of both.

The gist of this is that the more self-referential the conspiracy theory, the more like it is to be delusional.

Another article which expands on this idea is on Medscape: Ronald Pies and Joseph Pierre, “Believing in Conspiracy Theories is Not Delusional”—Medscape-Feb 04, 2021. According to them, delusions are fixed, false beliefs (something all psychiatrists learn early in residency) and usually self-referential. Conspiracy theories are frequently, but not necessarily, false, usually not self-referential, and based on evidence one can find in the world—often the internet. Conspiracy theories have blossomed during the COVID-19 pandemic. One of them is that it’s a government hoax. An important difference between the current pandemic and the flu pandemic of 1918 is the world wide web which makes it easier for many people to share the conspiracy theories.

Pies and Pierre describe a composite vignette of someone who has a conspiracy theory featuring many false beliefs about the COVID-19 vaccines ability to change one’s DNA, thinks that research results about the vaccines are faked, mistrusts experts, has no substance abuse or psychiatric history and no mental status exam abnormalities. He exhibits exposure to misinformation, biased information processing, and mistrusts authorities.

They would say he has no well-defined psychiatric illness and antipsychotic treatment (such as haloperidol) would not be helpful. However, similar to the approach with frankly delusional patients, they would argue against trying to talk the person out of his false beliefs. Instead, if the person can be engaged at all, the focus should be on trying to establish trust and respect, clarifying differences in the information sources available, and allowing time for the person to process the information. It would be more helpful to avoid confrontation and arguments, instead pointing out inconsistencies in the information the person has and contrasting it with facts. Countering misinformation with accurate information could be helpful.

There are two major routes to anti-vaccination beliefs of the severity under discussion here. One is the problem of conspiracy theories out there. The other is the florid delirium that can happen to patients admitted to ICUs with severe COVID-19 disease. The former may not be a classifiable mental illness per se, but the latter definitely is.

Haloperidol is not the main solution for either problem.