There’s been enough bad news. How about some good news? Have a look at the Dare to Discover campaign at The University of Iowa. It shines a light on young researchers who dream big. And that’s great for all of us!

Category: University of Iowa

Exercise or Weaponize My Privilege?

Back in November 2022, while on our way to the Stanley Museum of Art, we saw the two murals on the East Burlington Street Parking Ramp. It was the first time we saw them in person although photos were available last fall. The Little Village article published an article about them on September 30, 2021. It’s the Oracles of Iowa mural project, conceived by Public Space and the Center for Afrofuturist Studies partnered with the artists, Antoine Williams and Donte K. Hayes. The artists sought to stimulate a conversation in the community about how black and white people relate to each other.

The murals are painted on parking ramp at two locations along East Burlington Street. One says “Black Joy Needs No Permission” and the other says “Weaponize Your Privilege to Save Black Bodies.”

The Little Village article points out that a survey of public perception of the murals revealed that 64 percent of white respondents supported the murals while only 40-50 percent of minority respondents supported them. The stickler for minorities was the use of the word “weaponize” and the phrase “Black bodies,” which were thought to raise impressions of “violence” and dehumanization.

Because I’m a writer, retired psychiatrist, and a writer, the word “weaponize” made me wonder what other word might have been chosen in this context. The only definition of “weaponize” that I can find which makes sense to me is from Merriam-Webster: “to adapt for use as a weapon of war.”

I’m a retired physician, so I have a perspective on the “privilege” to “save” lives, and by extension to enhance health and well-being. I’m also Black. I grew up in Iowa and I can recall getting bullied and being called a “nigger.” I can remember my psychiatry residency days, which includes a memory of a patient saying “I don’t want no nigger doctor.” I didn’t have the option to switch patients with another resident. When I saw the patient on rounds, I did my best and every time the “nigger” word erupted, I left the room. It was one of a few episodes which were marked by frank racist attitudes.

I was given the University of Iowa Graduate Medical Education Excellence in Clinical Coaching Award in 2019, one of several esteemed colleagues to be honored in this way. Many of those who nominated me were white. It was one of many joyful experiences I had before my retirement in 2020, when the pandemic and other upheavals in society occurred, including the murder of Black persons, resulting in many consequences prompting the creation of the murals.

I have other memories. I was privileged to be given a scholarship to attend one of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) in this country, Huston-Tillotson College (now Huston-Tillotson University). It’s one of the oldest schools and is the oldest in Austin, Texas. The scholarship was supported by one of the local churches in my home town of Mason City. I don’t think it had any black members. Although I didn’t take my undergraduate degree from H-TU, it was one of the most valuable learning experiences in my life. It was the first time I was ever not the only Black student in the class. It was marked by both joy and a struggle to learn where I belonged.

The murals did for me what the artists hoped it would do. It stimulated me to reflect on the meaning of racializing life. They stir me to seek perspective on whether joy has any color and why anyone needs permission for it. And I believe I would rather exercise my privilege to respect and care for others than to weaponize anything, including my sense of humor.

More Thoughts on Physicians Going on Strike

I noticed Dr. H. Steven Moffic, MD had written another article in Psychiatric Times asking whether it’s time for psychiatrists to consider going on strike. Often the issue triggering discussions about this is the rising prevalence of physician burnout. I’ve already given my personal opinion about physicians going on strike and the short answer is “no.”

One of my colleagues, Dr. Michael Flaum, MD, recently delivered a Grand Rounds presentation about physician burnout. The title is “Everyone Wins—The Link Between Real Patient-Centered Care and Clinician Well-Being.”

Fortunately, I and other are able to hear the substance of his talk on the forum Rounding@Iowa. During these recorded presentations (for which CME can be obtained), Dr. Gerry Clancy, MD interviews clinicians on topics that are of special interest to medical professionals, but which can be educational for general listeners as well.

I remember meeting Dr. Flaum when I was a medical student. At the time, he was very involved in schizophrenia research. He’s been a very busy clinician ever since. As he says, while he may be Professor Emeritus now, he’s definitely not “retired.” He’s still very active clinically.

Dr. Flaum identifies both systems challenges and physician characteristics as important in the physician burnout issue. Interestingly, he bluntly calls the systems challenges as virtually unchangeable and focuses on bolstering the physician response to the system as the main controllable factor. His main tool is Motivational Interviewing, which is more of an interview style than a separate kind of psychotherapy.

I think the kind of approach that Dr. Flaum recommends, which you can hear about in the Rounding@Iowa presentation, is what most psychiatrists would prefer rather than going on strike. See what you think.

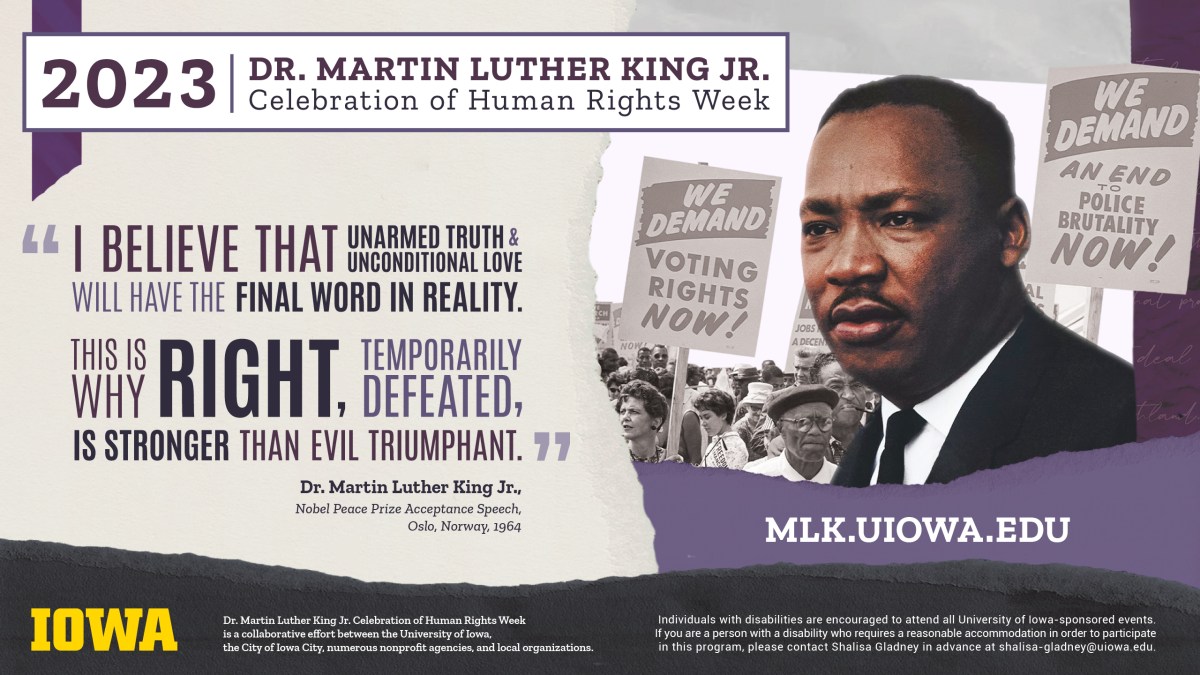

MLK Week Redux for the New University of Iowa Psychiatry Fellows

I discovered the University of Iowa Dept of Psychiatry had a very successful match, filling key residency slots in Child Psychiatry, Addiction Medicine, and Consultation-Liaison fellowships. Congratulations! That’s a big reason to celebrate.

This reminds me of my role as a teacher. I retired from the department two and a half years ago. But I’ll always remember how hard the residents and fellows worked.

And that’s why I’m reposting my blog “Remembering My Calling.”:

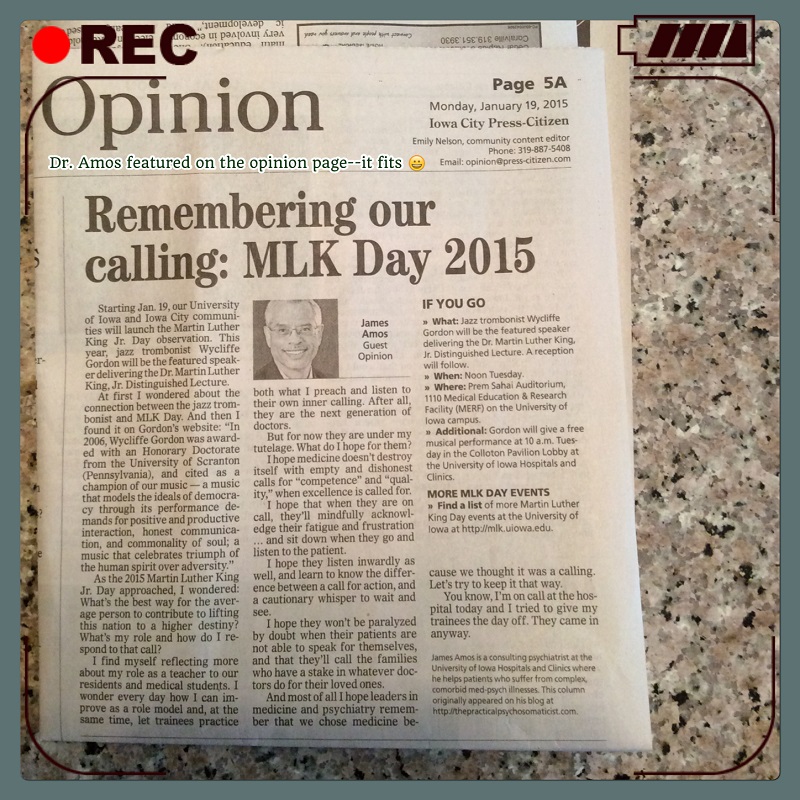

Back when I had the blog The Practical C-L Psychiatrist, I wrote a post about the Martin Luther King Jr. Day observation in 2015. It was published in the Iowa City Press-Citizen on January 19, 2015 under the title “Remembering our calling: MLK Day 2015.” I have a small legacy as a teacher. As I approach retirement next year, I reflect on that. When I entered medical school, I had no idea what I was in for. I struggled, lost faith–almost quit. I’m glad I didn’t because I’ve been privileged to learn from the next generation of doctors.

Faith is taking the first step, even when you don’t see the whole staircase.”

Martin Luther King, Jr.

As the 2015 Martin Luther King Jr. Day approached, I wondered: What’s the best way for the average person to contribute to lifting this nation to a higher destiny? What’s my role and how do I respond to that call?

I find myself reflecting more about my role as a teacher to our residents and medical students. I wonder every day how I can improve as a role model and, at the same time, let trainees practice both what I preach and listen to their own inner calling. After all, they are the next generation of doctors.

But for now they are under my tutelage. What do I hope for them?

I hope medicine doesn’t destroy itself with empty and dishonest calls for “competence” and “quality,” when excellence is called for.

I hope that when they are on call, they’ll mindfully acknowledge their fatigue and frustration…and sit down when they go and listen to the patient.

I hope they listen inwardly as well, and learn to know the difference between a call for action, and a cautionary whisper to wait and see.

I hope they won’t be paralyzed by doubt when their patients are not able to speak for themselves, and that they’ll call the families who have a stake in whatever doctors do for their loved ones.

And most of all I hope leaders in medicine and psychiatry remember that we chose medicine because we thought it was a calling. Let’s try to keep it that way.

You know, I’m on call at the hospital today and I tried to give my trainees the day off. They came in anyway.

An Old Post on Breaking Bad News

I’m reposting a piece about a sense of humor and breaking bad news to patients I first wrote for my old blog, The Practical Psychosomaticist about a dozen years ago. I still believe it’s relevant today. The excerpt from Mark Twain is priceless. Because it was published before 1923 (See Mark Twain’s Sketches, published in 1906, on google books) it’s also in the public domain, according to the Mark Twain Project.

Blog: A Sense of Humor is a Wonderful Thing

Most of my colleagues in medicine and psychiatry have a great sense of humor and Psychosomaticists particularly so. I’ll admit I’m biased, but so what? Take issues of breaking bad news, for example. Doctors frequently have to give their patients bad news. Some of do it well and others not so well. As a psychiatric consultant, I’ve occasionally found myself in the awkward position of seeing a cancer patient who has a poor prognosis—and who apparently doesn’t know that because the oncologist has declined to inform her about it. This may come as a shock to some. We’re used to thinking of that sort of paternalism as being a relic of bygone days because we’re so much more enlightened about informed consent, patient centered care, consumer focus with full truth disclosure, the right of patients to know and participate in their care and all that. I can tell you that paternalism is not a relic of bygone days.

Anyway, Mark Twain has a great little story about this called “Breaking It Gently”. A character named Higgins, (much like some doctors I’ve known) is charged with breaking the bad news of old Judge Bagley’s death to his widow. She’s completely unaware that her husband broke his neck and died after falling down the court-house stairs. After the judge’s body is loaded into Higgins’ wagon, Higgins is reminded to give Mrs. Bagley the sad news gently, to be “very guarded and discreet” and to do it “gradually and gently”. What follows is the exchange between Higgins and the now- widowed Mrs. Bagley after he shouts to her from his wagon[1]:

“Does the widder Bagley live here?”

“The widow Bagley? No, Sir!”

“I’ll bet she does. But have it your own way. Well, does Judge Bagley live here?”

“Yes, Judge Bagley lives here”.

“I’ll bet he don’t. But never mind—it ain’t for me to contradict. Is the Judge in?”

“No, not at present.”

“I jest expected as much. Because, you know—take hold o’suthin, mum, for I’m a-going to make a little communication, and I reckon maybe it’ll jar you some. There’s been an accident, mum. I’ve got the old Judge curled up out here in the wagon—and when you see him you’ll acknowledge, yourself, that an inquest is about the only thing that could be a comfort to him!”

That’s an example of the wrong way to break bad news, and something similar or worse still goes on in medicine even today. One of the better models is the SPIKES protocol[2]. Briefly, it goes like this:

Set up the interview, preferably so that both the physician and the patient are seated and allowing for time to connect with each other.

Perception assessment, meaning actively listening for what the patient already knows or thinks she knows.

Invite the patient to request more information about their illness and be ready to sensitively provide it.

Knowledge provided by the doctor in small, manageable chunks, who will avoid cold medical jargon.

Emotions should be acknowledged with empathic responses.

Summarize and set a strategy for future visits with the patient, emphasizing that the doctor will be there for the patient.

Gauging a sense of humor is one element among many of a thorough assessment by any psychiatrist. How does one teach that to interns, residents, and medical students? There’s no simple answer. It helps if there were good role models by a clinician-educator’s own teachers. One of mine was not even a physician. In the early 1970s when I was an undergraduate at Huston Tillotson University (when it was still Huston-Tillotson College), the faculty would occasionally put on an outrageous little talent show for the students in the King Seabrook Chapel. The star, in everyone’s opinion, was Dr. Jenny Lind Porter, who taught English. The normally staid and dignified Dr. Porter did a drop-dead strip tease while reciting classical poetry and some of her own ingenious inventions. Yes, in the chapel. Yes, the niece of author O. Henry; the Poet Laureate of Texas appointed in 1964 by then Texas Governor John Connally; the only woman to receive the Distinguished Diploma of Honor from Pepperdine University in 1979; yes, the Dr. Porter in the Texas Women’s Hall of Fame—almost wearing a very little glittering gold something or other.

It helps to be able to laugh at yourself.

1. Twain, M., et al., Mark Twain’s helpful hints for good living: a handbook for the damned human race. 2004, Berkeley: University of California Press. xiv, 207 p.

2. Baile, W.F., et al., SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist, 2000. 5(4): p. 302-11.

Giving Credit Where Credit is Due

Here’s another vintage post from around a decade ago after my former Psychiatry Dept chairperson, Dr. Robert G. Robinson and I published our book, Psychosomatic Medicine: An Introduction to Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry” in 2010.

Blog: Who Gets The Credit?

When I think about peak moments, I remember this guy back in junior high school who decided to try to break the Guinness Book of World Records for skipping rope. I don’t remember his name but the school principal and his teachers all agreed to let him do it during class hours. They marked out a little space for him in our home room. He was at it all day. And he was never alone because there was always a class in the room throughout the day. We didn’t get much work done because we couldn’t keep our eyes off him. It was mesmerizing. The longer he jumped, the more we hoped. We were very careful about how we encouraged him. We didn’t want to distract him and make him miss a jump. And so, we watched him with hope in our hearts. It was palpable. As he neared the goal, we were all crowded around him, teachers and students cheering. He was exhausted and could barely swing the rope over his head and lift his knees. When he made the time mark, we lifted him high above our heads and you could have heard us yelling our fool heads off for miles. Time stood still. He was a hero and we were his adoring fans. It didn’t occur to us to be jealous. His achievement belonged to all of us.

Another peak moment occurred more recently, when my colleagues and I published a book this summer. It’s my first book. It’s a handbook about consultation-liaison psychiatry which my department chairman and I edited, and the link is available on this page. This time, the effort was collaborative with over 40 contributors. The work took over 2 years and often, being an editor felt like herding cats. But we worked on it together. Many of the contributors were trainees working with seasoned psychiatrists who had much weightier research and writing projects on their minds, I’m sure. Like any first book, it was a labor of love. The goal was to teach fundamental concepts and pass along a few pearls about psychosomatic medicine to medical student, residents, and fellows. The book grew slowly, chapter by chapter. And when it was finally complete, this time the achievement was ours and again it belonged to all of us.

I made a lot of long-distance friends on the book project and occasionally get encouragement to do something else we could work together on. I suppose one thing everyone could do is to propose some kind of delirium early detection and prevention project at their own hospitals and chronicle that in a blog to raise awareness about delirium—sort of like what I’ve been trying to do here. We could share peak moments like:

- Getting the Sharepoint intranet site up and going so that group members can talk to each other about in discussion groups about how to hammer out a proposal, which delirium rating scale to use, or which management guidelines to use—and avoid the email storms.

- Being invited to give a talk about delirium at a grand rounds conference or regional meeting.

- Talking with someone who is interested in funding your delirium project (always a big hit).

That way if one of us falters, we always know that someone else is in there pitching. Copyrighting ideas and tools are fine. Hey, everybody has a right to protect their creative property. I’m mainly talking about sharing the idea of a movement to teach health care professionals, and patients about delirium, to help us all understand what causes it, what it is and what it is not, and how to prevent it from stealing our loved ones and our resources.

“It is amazing what you can accomplish if you do not care who gets the credit”-Harry Truman, Kansas Legislature member John Solbach, Ronald Reagan, Charles E. Montague, Benjamin Jowett, a Jesuit Father, a wise man, Edward T. Cook, Edward Everett Hale, a Jesuit Priest named Father Strickland.