I just rediscovered this old blog post below from 2010 in my files. The literature citations are dated, of course. I just wanted to reminisce about how I used to think through issues in consultation-liaison psychiatry. The post is old enough to contain the former term for the field-Psychosomatic Medicine.

“At the annual Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine (APM) meeting this year held on Marco Island, Florida, I heard Dr. Theodore Stern call Psychosomatic Medicine (PM) a “supraspecialty”. Usually it’s described as a subspecialty. I couldn’t find the word in Webster’s although “supra” comes from the Latin for “above, beyond, earlier”. One of the definitions is “transcending”. I tried to Google “supraspecialty” and came up empty. So I guess it’s a neologism. The context was a workshop on how to enhance resident and medical student education on Psychosomatic Medicine services. Dr. Stern coined the term while talking about the scope of practice of PM. As he went through the long list, it gradually dawned on me why “supraspecialty” as a title probably fits our profession. It’s mainly because it makes us, as psychiatrists, accountable for aspects of general and specialty medical and surgical care above and beyond that of Psychiatry alone.

As a member of this supraspecialty, we wrestle with some of the most intriguing questions about the core competencies of clinical care, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, medical knowledge, systems-based practice, and practice-based learning and improvement. These core competencies are a set of commandments, as it were, that teachers and learners are supposed to quantitatively assess in the service of producing competent doctors. While acknowledging the importance of qualitative assessment of the core competencies, Dr. Stern had the courage to criticize the assumption that quantitative assessment is even practicable. A qualitative assessment would probably be more practical.

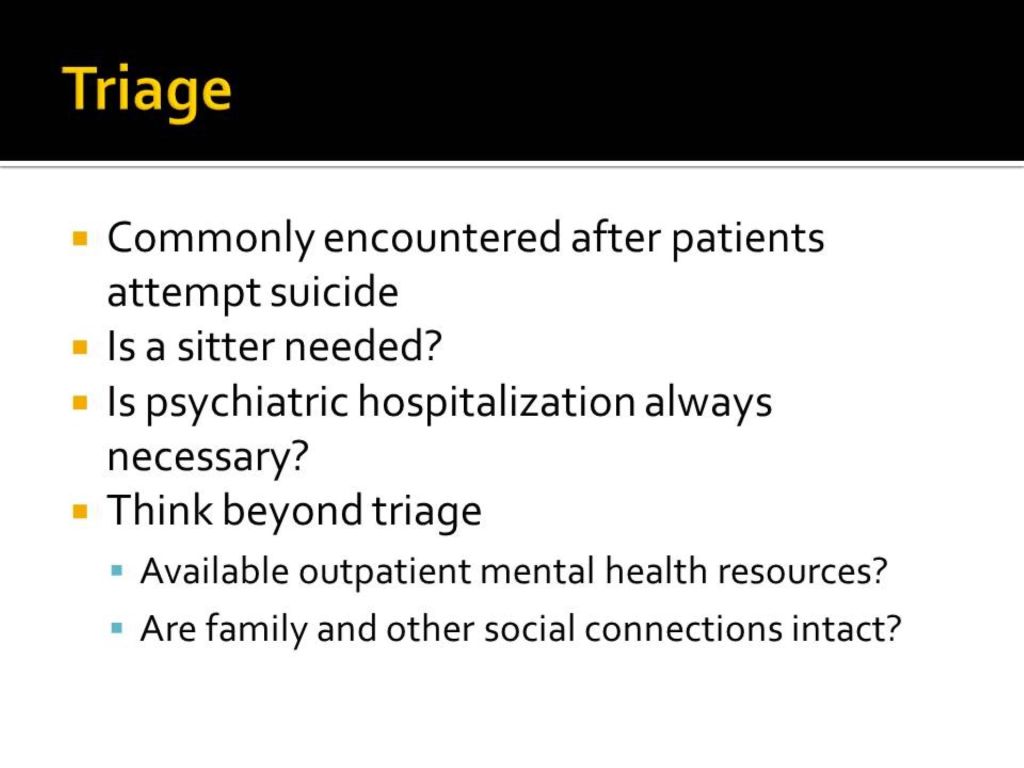

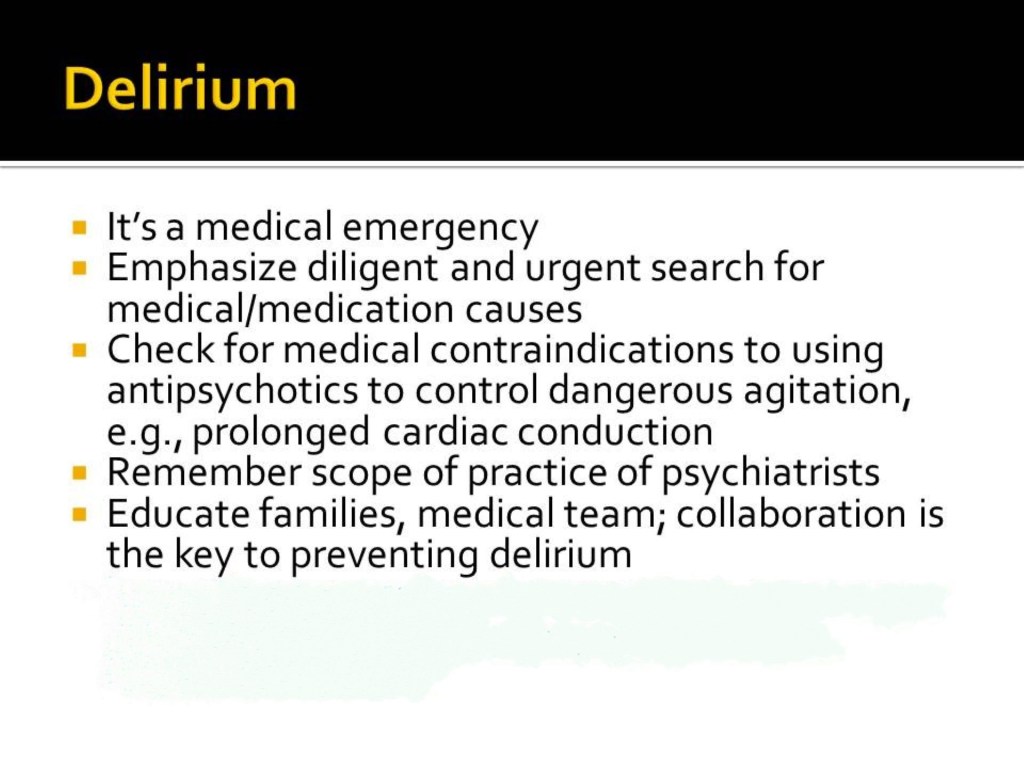

For example, how would one assess a trainee’s ability to digest, critically evaluate, communicate about, and integrate into local practice systems the small but growing knowledge about psychopharmacologic prevention of delirium? I am a bit surprised at the general enthusiasm among PM practitioners about pretreating patients with antipsychotics in an effort to prevent postoperative delirium. One of the more recent examples of a very small set of studies is the randomized controlled study by Larsen et al which showed that using Olanzapine prevented delirium in elderly joint-replacement patients[1]. The caveat that everyone seems to ignore is that the patients who got Olanzapine endured longer and more severe episodes of delirium. Dr. Sharon Inouye (who designed the Confusion Assessment Method or CAM for diagnosing delirium) has quoted George Washington Carver, “There is no shortcut to achievement”, cautioning against oversimplifying non-pharmacologic approaches to preventing delirium[2]. By extension, I’m suspicious of any recommendation that would reduce an intervention for preventing a syndrome as complex in etiology and pathophysiology as delirium to the administration of a single dose of a psychiatric drug either pre-op or post-op or both. Given the complexity of this issue, is there a quantifiable assessment method for core competencies that suffices? What I’d really like to see is how a trainee thought through the complex issues involved.

One other issue that would influence our ability to assess core competencies is the recent appearance of evidence which seems to show that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) when given with beta-blockers may increase mortality in heart failure patients[3]. The bulk of the research evidence in the last couple of decades impels psychiatrists and cardiologists alike to have a low threshold for prescribing SSRIs to patients with heart disease in order to prevent depression. Again, in this context, is there a suitable quantifiable assessment for gauging whether or not a trainee has mastered the core competencies adequately? I would rather hear or read a trainee’s reflections on how to decide for oneself what the safest course of action would be under particular circumstances, and then how to convey that to our colleagues in Cardiology.

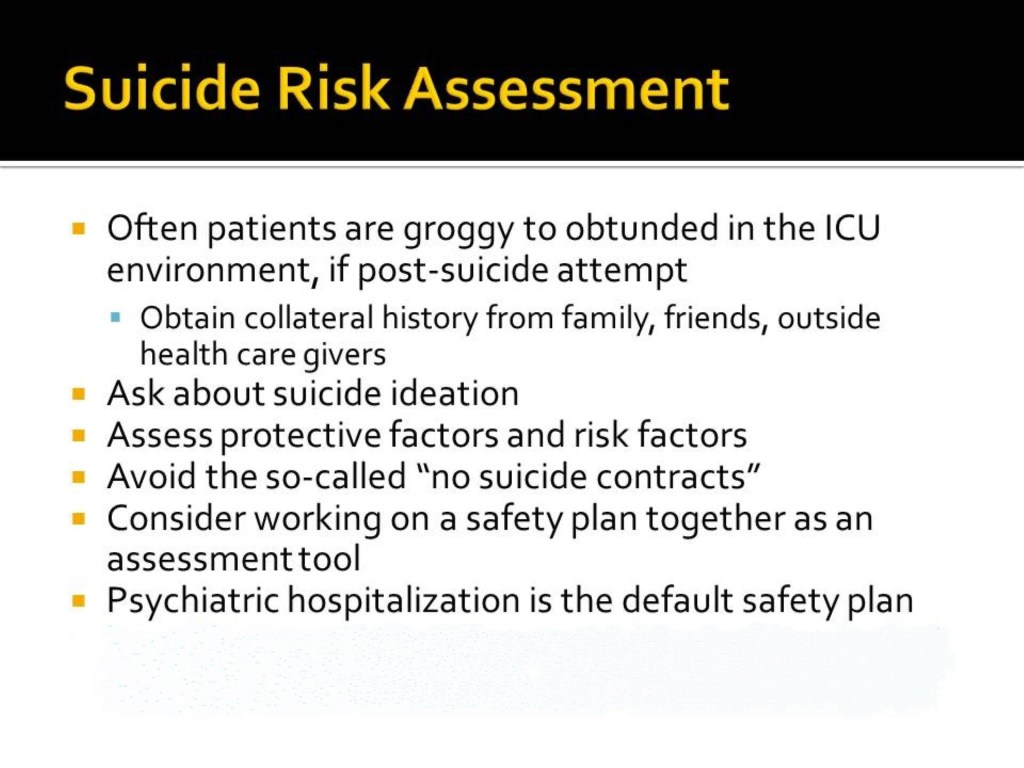

And is there a reliably quantifiable way to assess how a PM consultant (trainee or not) evaluates and recommends treatment for an ICU patient who develops catatonia postoperatively in the context of abrupt withdrawal of previously prescribed benzodiazepine, in the face of recent evidence that Lorazepam is an independent predictor of delirium in the ICU[4, 5]?

These situations tax the medical and psychiatric knowledge, treatment and communication skills and wisdom of master and learner alike. Is it possible to mark a check box on a rating scale to assess performance? And would that give us and our patients the ability to tell whether a doctor has the wherewithal to discern what kind of disease the patient has and what kind of patient has the disease, to do the thing right and to do the right thing?

All of these examples make me wonder whether or not quantifiable assessment of every core competency in the supraspecialty of PM is realistic or even desirable.

1. Larsen, K.A., et al., Administration of olanzapine to prevent postoperative delirium in elderly joint-replacement patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Psychosomatics, 2010. 51(5): p. 409-18.

2. Inouye, S.K., et al., NO SHORTCUTS FOR DELIRIUM PREVENTION. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2010. 58(5): p. 998-999.

3. Veien, K.T., et al., High mortality among heart failure patients treated with antidepressants. Int J Cardiol, 2010.

4. Brown, M. and S. Freeman, Clonazepam withdrawal-induced catatonia. Psychosomatics, 2009. 50(3): p. 289-92.

5. Pandharipande, P., et al., Lorazepam is an independent risk factor for transitioning to delirium in intensive care unit patients. Anesthesiology, 2006. 104(1): p. 21-6.”