Today is the 60th anniversary of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C.

I was too young to remember it. However, I have a deep appreciation of the meaning it has not just for Black people, but for all of us. It’s not difficult to broaden the implication for all people.

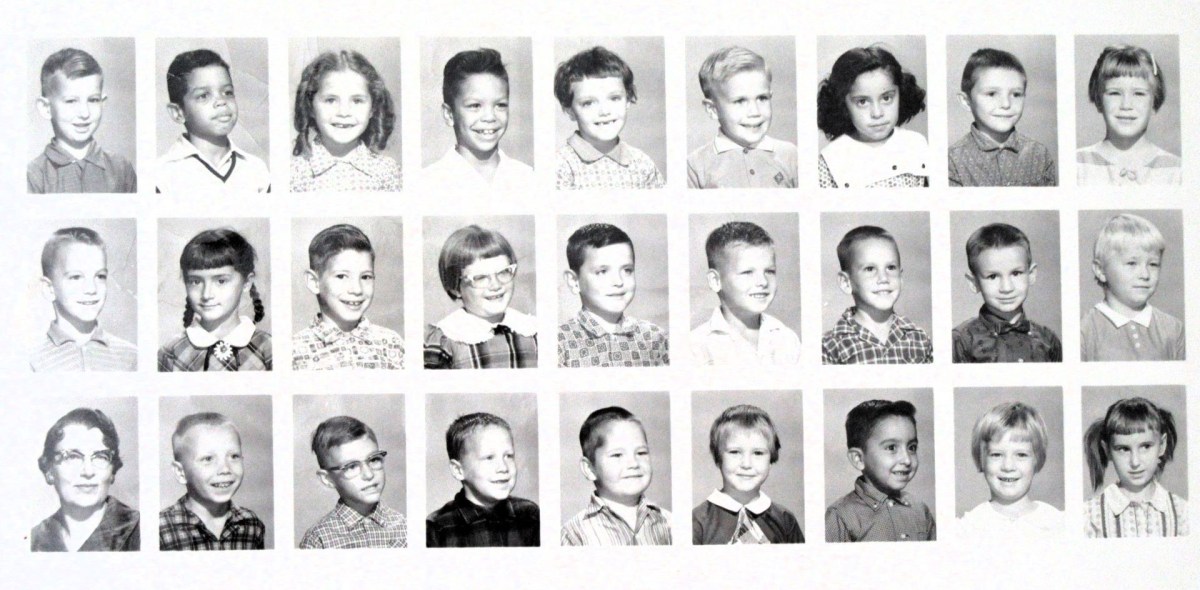

My personal reflection about this started this morning with a look at one of my primary school class pictures. I’m the handsome guy 2nd from the left in the top row. The other kids of color in the photo are Latino.

The photo shows not just a group of kids. It also illustrates, just by chance, pretty closely the percentage of black persons in the state of Iowa as of the 2021 U.S. census, about 4%. Historically though, in the county in which I was living at that time, the percentage of nonwhite persons was listed at 0.4%. This was a 28% drop from the previous decade. In 1980, the percentage of Black people in the state was only 1.8%. As near as I can tell from the web, the current percentage of Black people as of the most recent data is 3.74% (possibly as of 2021).

My father was black and my mother was white. In Iowa, the law against miscegenation (marriage between blacks and whites) was repealed in 1839. On the other hand, my parents got their marriage license in 1954 in Watertown, South Dakota—which was 3 years prior to when that state repealed its law against interracial marriage. Right below the license, though, is a certificate of marriage marked State of South Dakota in Codington County. It certifies that my parents were married in Mason City, Cerro Gordo County in the state of Iowa.

I’m not going to try to puzzle that one out. My mother kept a lot of old photos and legal records that anchor me in my personal history.

I have photos of my father with me and my brother, Randy. I also have photos of my mother with me and my brother.

What I don’t have are photos of all of us together. It’s understandable to ask why. I wonder if it has something to do with the culture and mindset of the time. Why was it not possible to find someone, black or white, to snap a family photo of us together?

We can pass legislation repealing anti-miscegenation laws as well as other laws to protect civil rights. That is a necessary (but perhaps insufficient) step toward non-exclusion of certain groups of people from basic human rights.

Ashley Sharpton, who is an activist with the National Action Network and daughter of Reverend Al Sharpton, said that Americans need to “turn demonstration into legislation.”

I agree with her. On the other hand, I also wonder what more has to happen in the minds of all of us to turn legislation into transformation—of our personal implicit biases, which are not in themselves always bad or inescapable.

And since we’re into rhyming, what about asking another question? Can we turn demonstration into legislation while encouraging transformation without bitter confrontation?