I got a nice, if puzzling surprise today. At a faculty meeting I was recognized for my 10-year anniversary of service at our hospital. It’s an important milestone, even if it is wrong. They scheduled this small event a couple of months ago, but I was too busy on the psychiatry consult service to break away. I also usually carry the pager for the trainees during the noon hour when the faculty meetings are held.

The 10-year anniversary recognition was very kind—except that I’ve been here for twenty odd years, not counting residency and medical school.

In all fairness, my department knows that and we shared a few jokes about it. I guess I should clarify that I have left the university for private practice a couple of times, which interrupts the years of service recognition timelines.

I was gone both times for a total of less than 12 months—just sayin’. I returned for a few reasons, although mainly because I missed teaching.

Anyway, I showed up at the faculty meeting, albeit a little guilty looking because I’m usually too busy to attend. My department chair arrived and said that she had to run back to get my “statue.”

That jarred me. Several years ago, when I had my first blog, The Practical Consultation-Liaison (C-L) Psychiatrist, I used to kid my readers that someday a statue of me would be erected in the university Quad. It would be made of Play-Doh.

And that’s why I asked her as she turned to leave, “Is it made of Play-Doh?” She looked puzzled and I didn’t really think I could explain in a way that wouldn’t make me look like I’d been smoking something illegal.

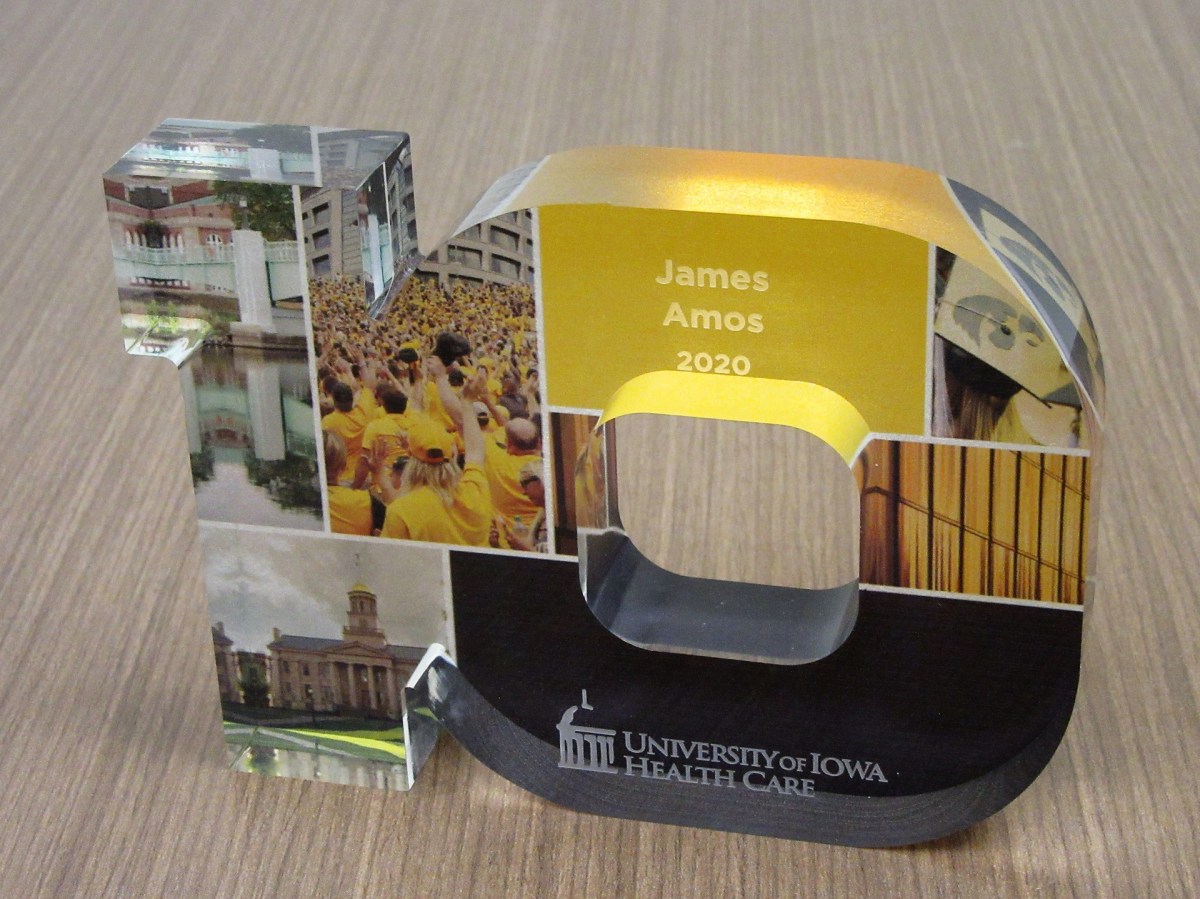

The “statue” is a handsome little sculpture of the number 10, standing for 10 years of service. It has color photos embedded in it of various aspects of academic life at the University of Iowa, many of which I’ve had the privilege of enjoying in the 30 odd years my wife, Sena, and I have been in Iowa City.

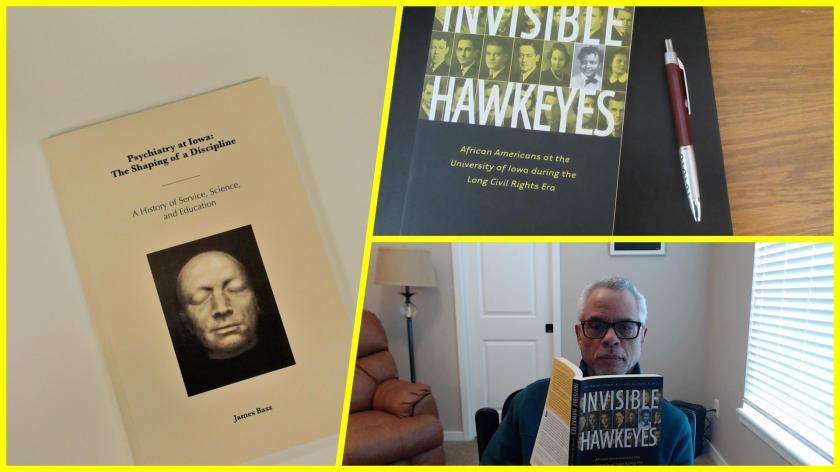

Just before the meeting, I had walked up to the 8th floor (I always take the stairs) to the psychiatry department offices to see if I could get a copy of the recently published history of the department, Psychiatry at Iowa: The Shaping of a Discipline: A History of Service, Science, and Education, written by James Bass.

Mr. Bass interviewed many people in the department, including me. I didn’t expect that my perspective on the consultation service, the clinical track, or my race would even get mentioned. However, 2 out of 3 made it into print.

It didn’t really surprise me that my being African American was not mentioned. I think I’m probably the only African American faculty member of the department in its 100-year history, at least until very recently.

It reminded me of another book that I just acquired, Invisible Hawkeyes: African Americans at the University of Iowa during the Long Civil Rights Era, edited by Lena M. Hill and Michael D. Hill.

In a small way, I’m making the invisible visible.

Making the invisible visible

And also, because it’s great for my ego, I’m going to quote what Bass wrote about me in Chapter 5, The New Path of George Winokur, 1971-1990:

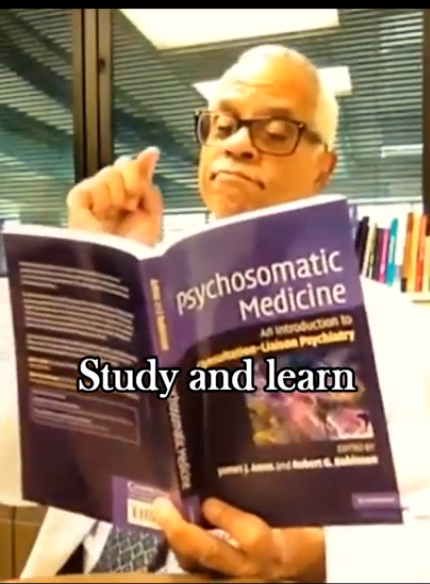

“If in Iowa’s Department of Psychiatry there is an essential example of the consultation-liaison psychiatrist, it would be Dr. James Amos. A true in-the-trenches clinician and teacher, Amos’s potential was first spotted by George Winokur and then cultivated by Winokur’s successor, Bob Robinson. Robinson initially sought a research gene in Amos, but, as Amos would be the first to state, clinical work—not research—would be Amos’s true calling. With Russell Noyes, before Noyes’ retirement in 2002, Amos ran the UIHC psychiatry consultation service and then continued on, heroically serving an 811-bed hospital. In 2010 he would edit a book with Robinson entitled Psychosomatic Medicine: An Introduction to Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry.” (Bass, J. (2019). Psychiatry at Iowa: A History of Service, Science, and Education. Iowa City, Iowa, The University of Iowa Department of Psychiatry).

In chapter 6 (Robert G. Robinson and the Widening of Basic Science, 1990-2011), he mentions my name in the context of being one of the first clinical track faculty in the department. In some ways, breaking ground as a clinical track faculty was probably harder than being the only African American faculty member in the department.

As retirement approaches this coming June, I look back at what others and I worked together to accomplish within consultation-liaison psychiatry. The challenges were best described by a former President of the Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry, Thomas Hackett (this quote I helped find for James Bass and anyone can view it on the Internet Archive):

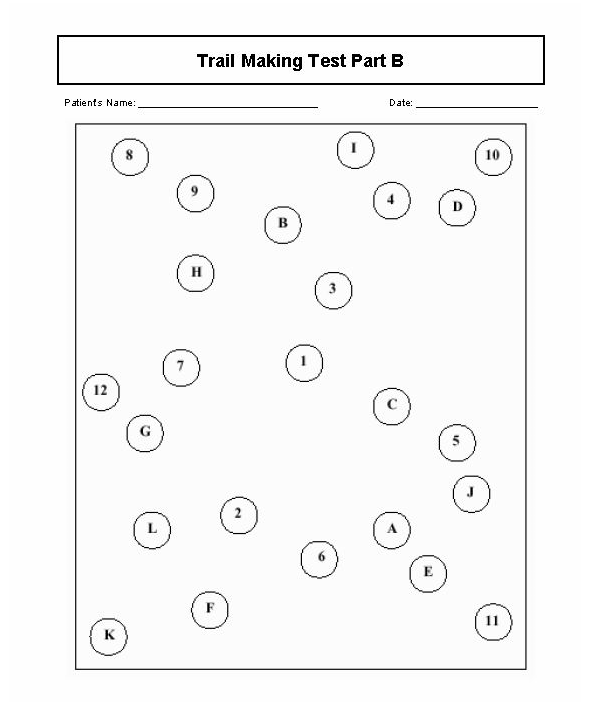

“A distinction must be made between a consultation service and a consultation liaison service. A consultation service is a rescue squad. It responds to requests from other services for help with the diagnosis, treatment, or disposition of perplexing patients. At worst, consultation work is nothing more than a brief foray into the territory of another service, usually ending with a note written in the chart outlining a plan of action. The actual intervention is left to the consultee. Like a volunteer firefighter, a consultant puts out the blaze and then returns home. Like a volunteer fire brigade, a consultation service seldom has the time or manpower to set up fire prevention programs or to educate the citizenry about fireproofing. A consultation service is the most common type of psychiatric-medical interface found in departments of psychiatry around the United States today.

A liaison service requires manpower, money, and motivation. Sufficient personnel are necessary to allow the psychiatric consultant time to perform services other than simply interviewing troublesome patients in the area assigned. He must be able to attend rounds, discuss patients individually with house officers, and hold teaching sessions for nurses. Liaison work is further distinguished from consultation activity in that patients are seen at the discretion of the psychiatric consultant as well as the referring physician. Because the consultant attends social service rounds with the house officers, he is able to spot potential psychiatric problems.”— Hackett, T. P., MD (1978). Beginnings: liaison psychiatry in a general hospital. Massachusetts General Hospital: Handbook of general hospital psychiatry. T. P. Hackett, MD and N. H. Cassem, MD. St. Louis, Missouri, The C.V. Mosby Company: 1-14.

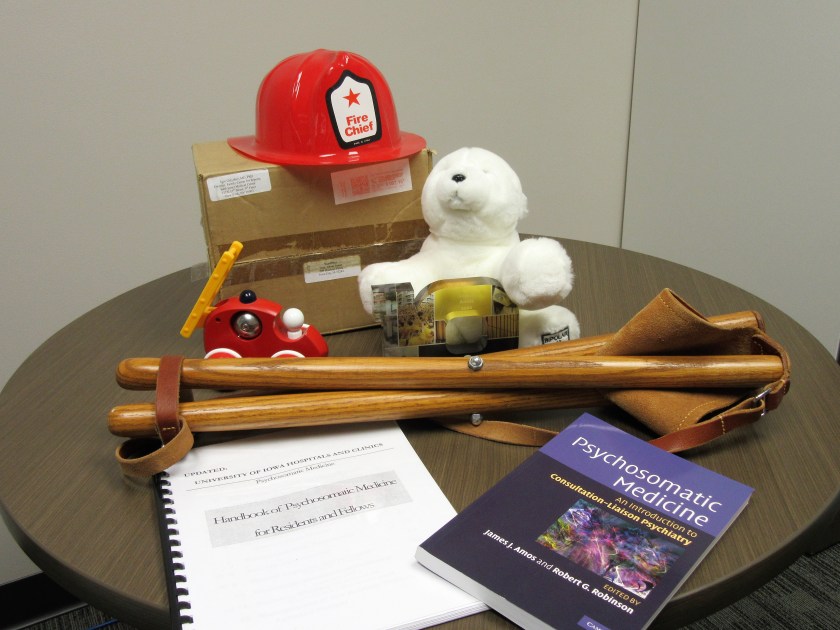

I have what seems like precious few mementos of my sojourn here in the department and, indeed, on this earth. I have a toy fireman’s helmet I found hanging in a plastic sack on my office doorknob one day. It was a gift from a Family Medicine resident who rotated on the consult service and who learned why I called it a fire brigade.

For the same reason, I have a toy fire truck, sent to me by a New York psychoanalyst who was also a blogger.

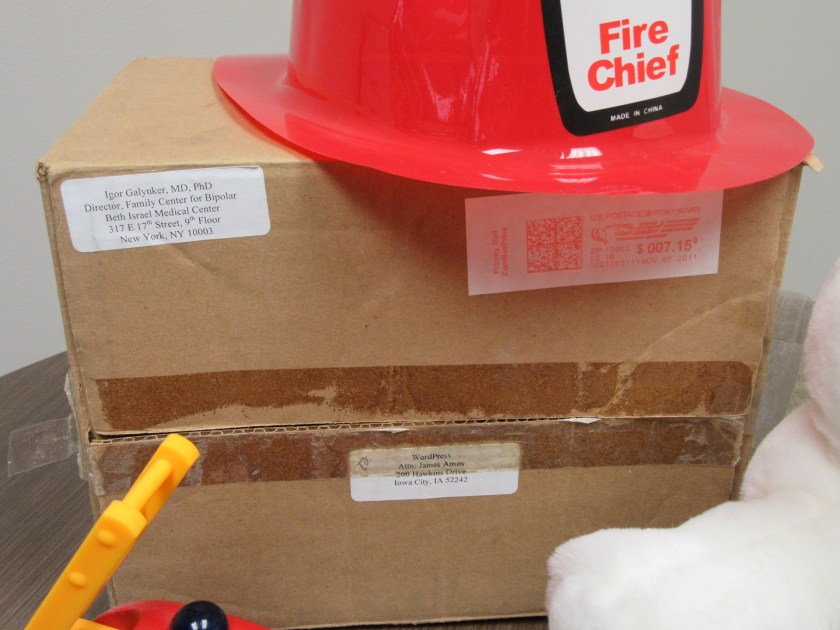

I have Bumpy the Bipolar Bear, believe or not, sent to me by psychiatrist, Dr. Igor Galynker, about whose emergency room suicide risk assessment method I had blogged about several years ago. C-L psychiatrists do a lot of suicide risk assessments in the hospital and the clinics. I still have the box with the address to me:

WordPress

Attn: James Amos

200 Hawkins Drive

Iowa City, IA 52242

I have my first homemade handbook for C-L Psychiatry and the published handbook that eventually replaced it. Thank goodness the leaders of the Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry listened to the membership and changed the name from Psychosomatic Medicine to C-L Psychiatry.

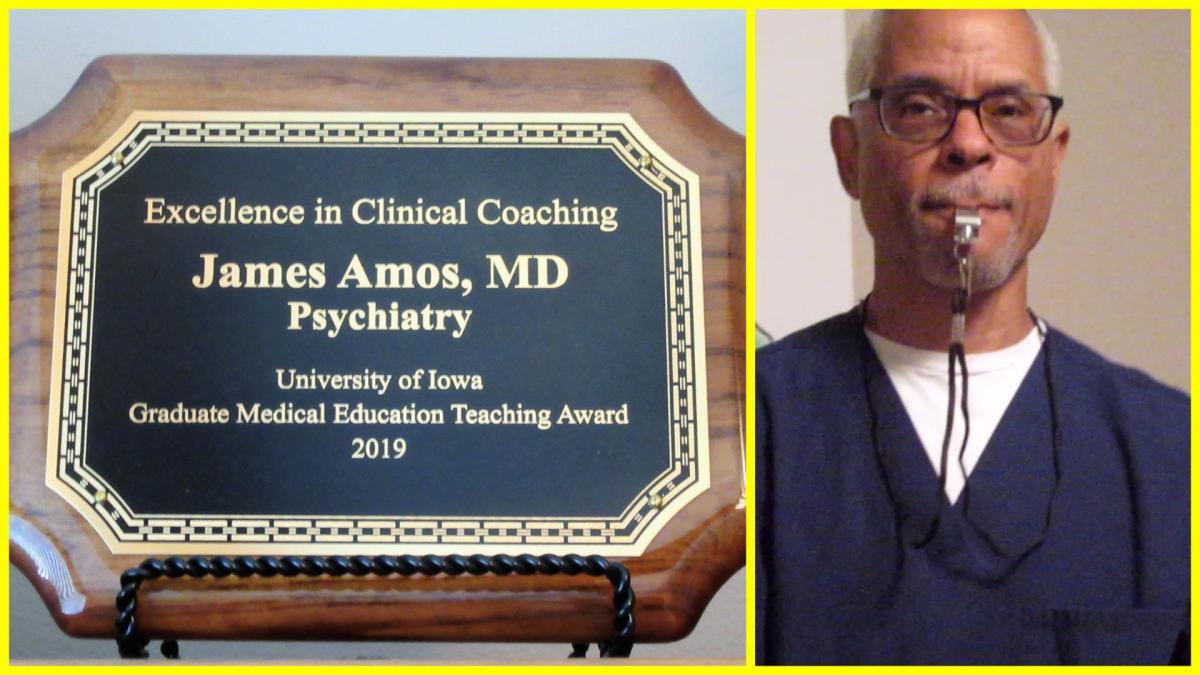

I have an award for being an excellent clinical coach.

And I have my little camp stool, which a colleague who is a surgeon and emergency medicine physician gave me and which allows me to sit with my patients anywhere in the hospital, so that I don’t have to stand over them.

It will all fit in a cardboard box on my last day—the next milestone.