Retiring takes practice, like a great many skills. I know it’s puzzling to think of retiring as a skill. Skill building feels awkward at first and with time, managing the transition slowly feels more natural. At least that’s what I hope about this retirement thing.

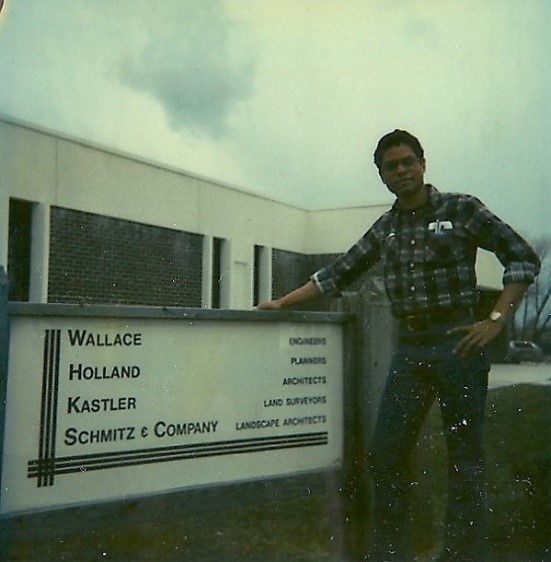

I remember way back in the day of the dinosaurs when I was working for consulting engineers. It was my first real job. I had to learn many new skills in my role as a land surveyor assistant. I started out mainly as a rear chain man and a rod man. These are special tools to measure distance and elevation.

Throwing a chain is a term for wrapping a 100-foot chain. This skill is almost impossible to describe just by writing about it. I could find only one fairly straightforward video about it which shows the proper technique.

The last part of it, which is collapsing the figure 8 shape of the chain into a circle is done almost by feel and was easier when I didn’t think about it. Overthinking a technique or skill can get in the way of just doing it.

I did those kinds of things every day for years. I gradually learned other skills until I felt like I fit in with land surveyors. I got a lot of satisfaction out of this kind of work when I was a young man.

But when it was time to move on to college, I found it difficult to adjust initially. I was used to doing work with my hands more than my head. It felt awkward to be in a class with a lot of students who were much younger than I was.

I made the transition and moved on eventually to medical school. That was another difficult transition in which I needed to develop new skill sets. It felt so unnatural that I thought of going back to working for consulting engineers.

But I hung in there and finally settled on being a consultation-liaison psychiatrist. I’ve gone from a consulting engineer world to a consulting psychiatrist world. They both involve consulting. The WHKS company I used to work for has a vision, purpose, and values that are arguably similar to consultation psychiatry in some ways.

I try to listen carefully to my patients and help them shape a better understanding of themselves and their relationships.

I try to provide consultation that ultimately benefits patients, sustains a healthy interpersonal environment for them and clarifies their values, the things that mean the most to them.

I value listening; communicating; being of service to both patients and their physicians, nurses, and other health care professionals; being practical (I used to write the blog The Practical C-L Psychiatrist after all); and I like to think I’m sometimes innovative in my approach to psychiatric assessment, patient care, and teaching the next generation of doctors.

I’ve been a physician for over 26 years counting residency. And of course I spent 4 years in medical school. Retirement is a little jarring and doesn’t yet feel completely natural, frankly. I keep waiting for the chain to just fall into place.

I’m probably overthinking it.