Today being Martin Luther King Day, I’m reminiscing a little about my short time as a student at Huston-Tillotson College (one of this country’s HBCUs, Huston-Tillotson University since 2005) in Austin, Texas. It’s always a good idea to thank your teachers. I never took a degree there, choosing to transfer credit to Iowa State University toward my Bachelor’s, later earning my medical degree at The University of Iowa.

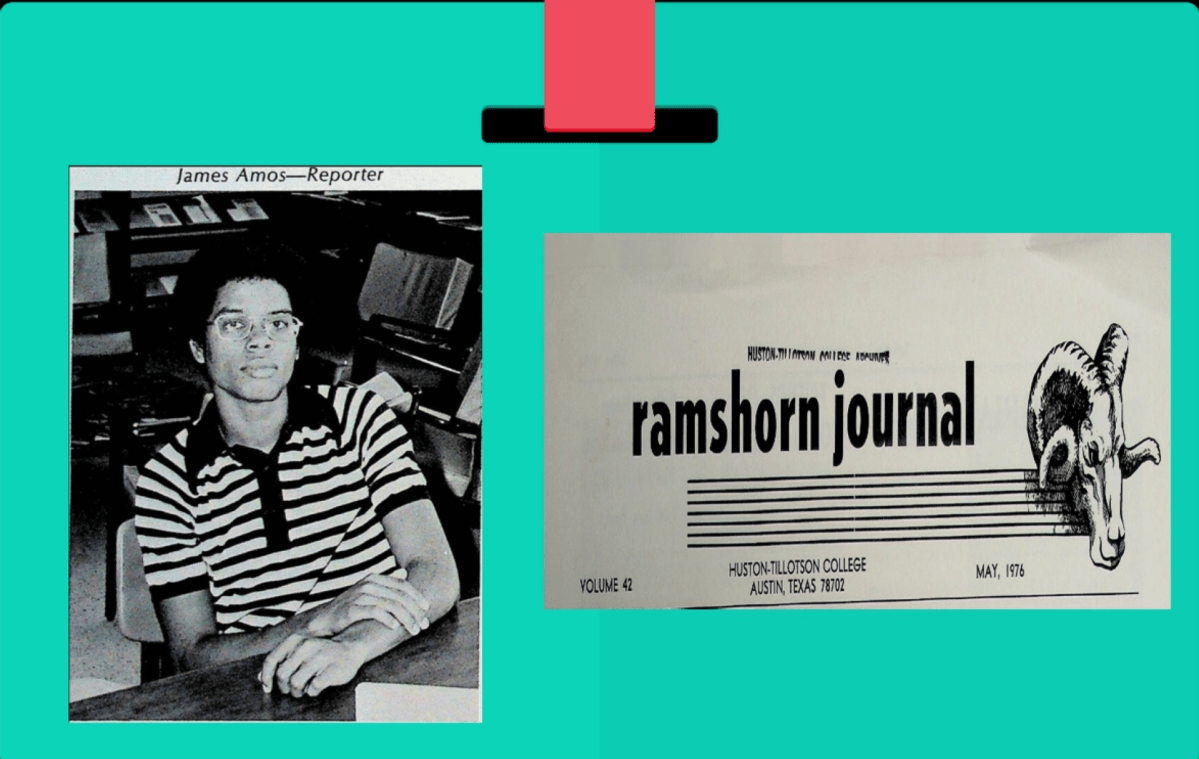

However, I was a reporter for the college newspaper, The Ramshorn Journal. That’s where the featured image comes from.

Although I didn’t come of age at HT, I can see that a few of my most enduring habits of thought and my goals spring from those two years at this small, mostly African-American enrollment college. I learned about tenacity to principle and practice from a visiting professor, Dr Melvin P. Sikes, in Sociology (from the University of Texas) who paced back and forth across the Agard-Lovinggood auditorium stage in a lemon-yellow leisure suit as he ranted about the importance of bringing about change.

He was a scholar yet decried the pursuit of the mere trappings of scholarship, exhorting us to work directly for change where it was needed most. He didn’t assign term papers, but sent me and another freshman to the Austin Police Department. The goal evidently was to make them nervous by our requests for the uniform police report, which our professor suspected might reveal a tendency to arrest blacks more frequently than whites.

He wasn’t satisfied with merely studying society’s institutions; he worked to change them for the better. Although I was probably just as nervous as the cops were, the lesson about the importance of applying principles of change directly to society eventually stuck. I remembered it every time I encountered push-back from change-resistant hospital administrations.

As a clinician-educator I have a passion for both science and humanistic approaches in the practice of psychiatry. Dr. James Means struggled to teach us mathematics, the language of science. He was a dyspeptic man, who once observed that he treated us better than we treated ourselves. Looking back on it, I can see he was right.

Dr. Lamar Kirven (or Major Kirven because he was in the military) also modeled passion. He taught black history and he was always excited about it. When he scrawled something on the blackboard, you couldn’t read it but you knew what he meant.

And there was Dr. Hector Grant, chaplain and professor of religious studies, and devoted to his native Jamaica. He once said to me, “Not everyone can be a Baptist preacher.” He tried to explain that my loss of a debate to someone who won simply by not allowing me a word in edgewise was sometimes an unavoidable result of competing with an opponent who is simply bombastic.

Dr. Porter taught English Literature and writing. She also tried to teach me about Rosicrucian philosophy for which she held a singular passion. Not everyone can be a Rosicrucian philosopher. But it prepared the way for me to accept the importance of spirituality in medicine.

I didn’t know it back in the seventies, but my teachers at HT would be my heroes. We need heroes like that in our medical schools, guiding the next generation of doctors. We need them in a variety of leadership roles in our society. Most of my former HT heroes are not living in the world now. But I can still hear their voices.