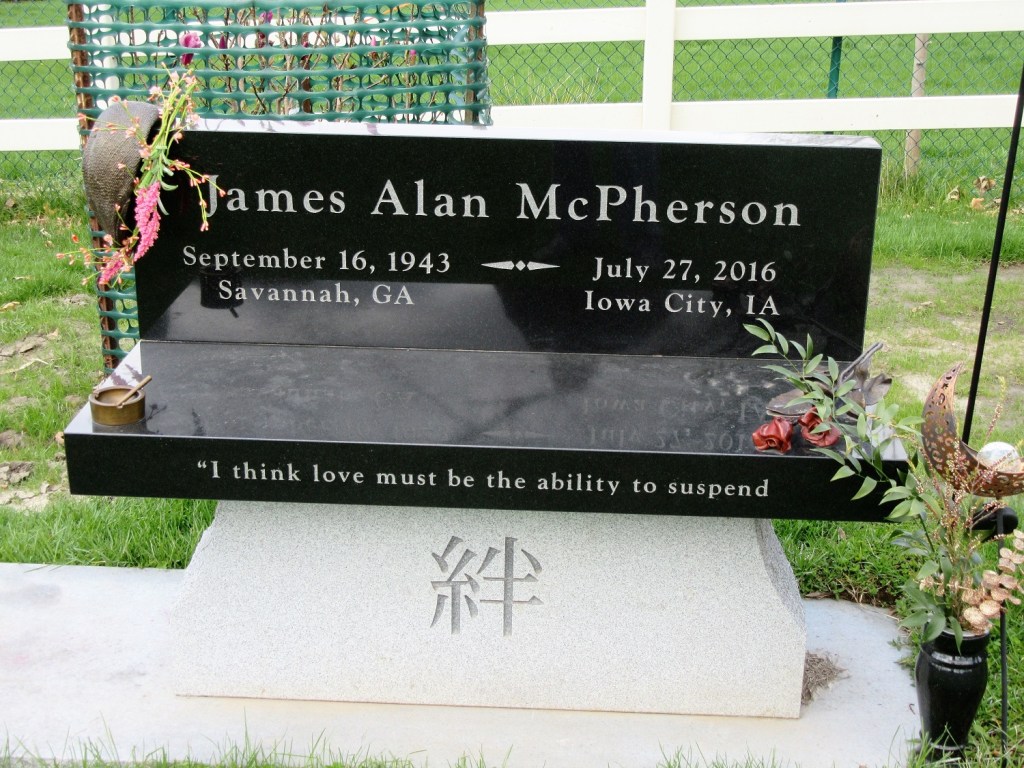

We don’t usually make trips to Oakland Cemetery (or any cemetery for that matter), but today we made an exception to find the grave of James Alan McPherson, the first African American to win a Pulitzer Prize for fiction and longtime Iowa Writers’ Workshop faculty who died in 2016 and for whom an Iowa City park was renamed a month ago.

We never met McPherson, although we are reading a couple of his books (Elbow Room, the Pulitzer Park winning work, and Hue and Cry) and just visited the James Alan McPherson Park on Monday this week.

This trip brought back happy memories right away. It’s not the first time we’ve been to Oakland Cemetery. In 2015 and 2016 we took the same route, parking at Happy Hollow Park on Brown Street and walking east to find the Black Angel. The main reason for going to Happy Hollow Park back then was not so much to see the Black Angel, but for two Psychiatry Department Faculty vs Resident Matball games at Happy Hollow Park. Matball is an imaginative combination of kickball and baseball using large mats for bases and a kickball for pitching, which the hitter actually kicks and runs the bases.

I was on faculty but didn’t play, which I thought would help them win. It was very hot both years. Faculty lost both years. There was another match in 2017 which I didn’t attend, and which I think faculty also lost.

But it was great fun. I don’t remember who put the 2015 trophy won by the residents in a bowl of red (possibly strawberry, I didn’t eat any) Jell-O. That took imagination. It was a stroke of genius, but was not repeated after the following two losses. There have been no Matball games since then.

Anyway, we visited the Black Angel. I think I left some loose change at the foot of the sculpture, which is traditional I think, for good luck. The Black Angel has a very complicated story, which is in many cases, fueled by superhuman imagination. The stories get more complicated every year and the legends have been developing since the 9-foot statue with 4-foot pedestal was created in 1912.

Actually, the Black Angel is often used as a point of reference for the rest of the cemetery. That’s how we used it today to find McPherson’s grave, which is said to be in a place called the poets’ corner where many other artists, including Writers’ Workshop faculty, are buried.

The easiest way to find the Black Angel is probably to approach the cemetery from the west and head east to the intersection of Brown and Governor Streets, where there’s a big sign for Oakland Cemetery. There’s a map next to the cemetery office. We could not find any place marked “poets’ corner.” But the Black Angel is clearly marked.

You’ll notice you can drive through the cemetery, but the paved road is about the width of a car. It’s actually more like a service road, just right for riding mowers, but a little narrow for cars. There is no parking lot we could find, which is why we parked at Happy Hollow Park.

As you reach the Black Angel, you’ll notice one of her wings is raised at a right angle from her body. It points roughly North. You need to go in the opposite direction to find poets’ corner. As you pass the Black Angel, take the second path to the right and simply follow it around, moving south past the University of Iowa Deeded Body Program monument to a section marked with a narrow post labeled “Oak Green.” That’s where you’ll find McPherson’s headstone.

The headstone is easy to pick out; it’s an imaginative work of art. The black rectangular stone is decorated with clever sculptures including his signature car cap, two roses, and even a cigarette in an ashtray. He was a smoker. I don’t know what the characters on the pedestal mean.

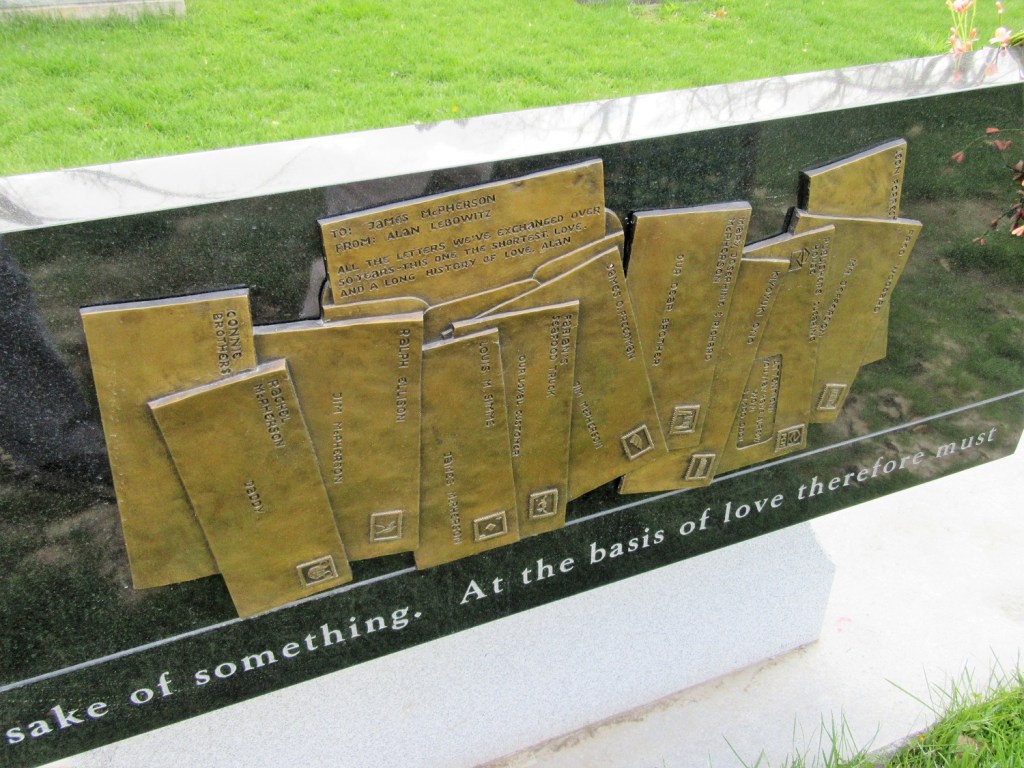

On the back of the stone are many carved envelopes indicating McPherson’s mail correspondence with many loving friends and family—and beyond. There is a sense of humor and imagination here too. One of the envelopes is from “Publisher’s Clearinghouse” and the recipient section says “ATTENTION: You may have already won $1,000,000!” I can just picture Ed McMahon! Another is from “Fabian’s Seafood Truck” to “Our Loyal Customer.” I didn’t realize it while we were there, but when we got home, it occurred to me that as we were driving home from James Alan McPherson Park, we saw a big refrigerated truck where seafood was being sold; it was next to the Dairy Queen on Riverside Street. I searched Fabian Seafood on the web and found a picture that exactly matched what we saw.

Around the edge of the headstone was an inscription that to read in its entirety you have to walk all the way around the monument because the words are carved in the front, sides and back:

“I think love must be the ability to suspend one’s intelligence for the sake of something. At the basis of love therefore must live imagination.” This is a quote from McPherson. He also wrote in his essay “Pursuit of the Pneuma” about “an ancient bit of spiritual wisdom” which denies that God rested on the seventh day after creating all existence. Instead, God created imagination and gave this gift to his human creations, enabling us to wield an integrative kind of power—which is what love can do.

Imagination therefore lives in Oakland Cemetery.