Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) are in the news lately. It reminds me of the short time I spent at Huston-Tillotson College. It was renamed Huston-Tillotson University (H-TU) in 2005. I was there in the mid-1970s.

A new President and CEO was just named this month, Dr. Melva K. Williams. And H-TU was recently added to the National Register of Historic Places last month. It has been renovated and modernized. Pictures show a well-kept campus pretty much as I remember it over 40 years ago. I didn’t graduate from H-TU, but instead transferred credits to Iowa State University where I graduated in 1985.

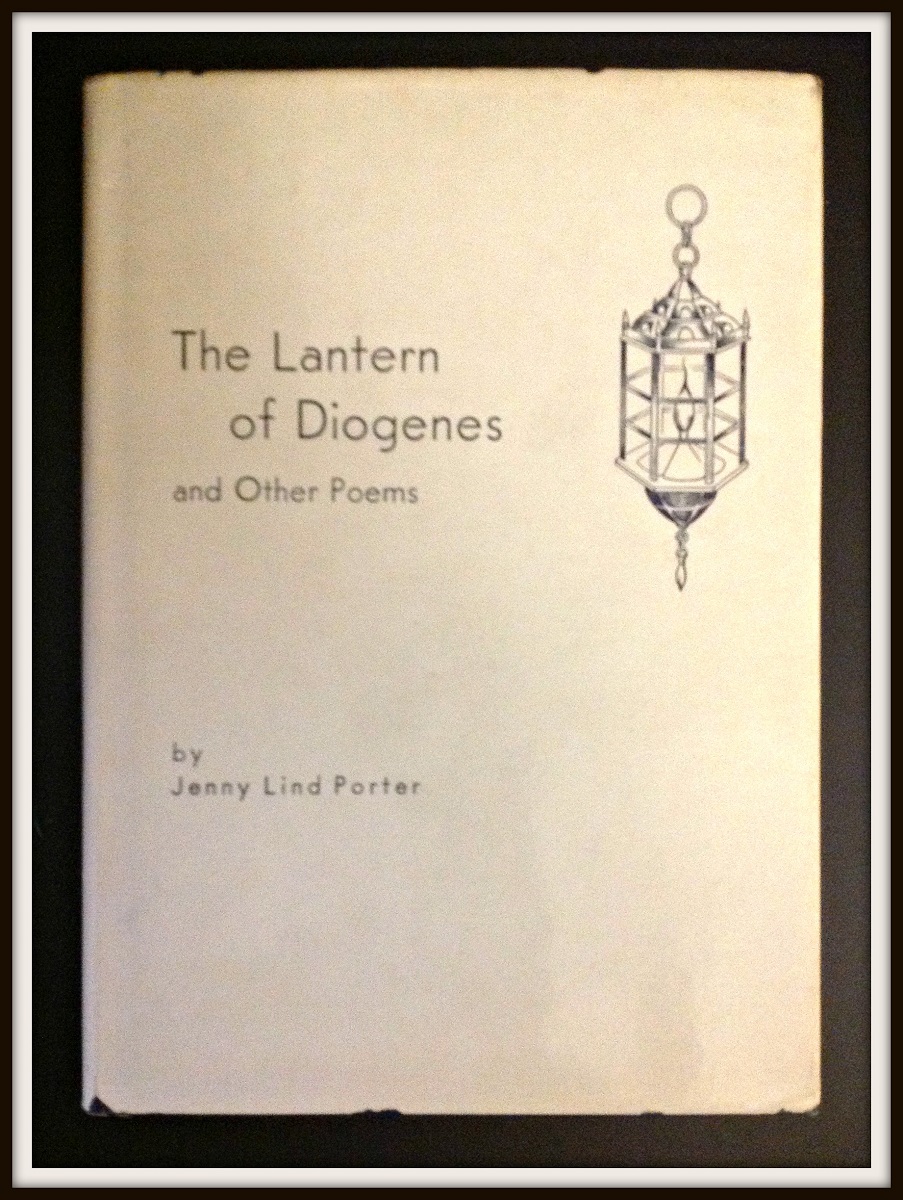

My favorite teacher was Dr. Jenny Lind Porter-Scott, who was white, taught English Literature. Another very influential teacher was Reverend Hector Grant who was black. He taught philosophy and religion. He was instrumental in recruiting me to matriculate at H-TU. He helped me to process my loss on the debating team when the question was whether or not the death penalty played any role in the reduction of crime.

My opponent won the debate mainly because he talked so much, I couldn’t get a word in edgewise. I can’t remember which side of the question I argued, but I thought I could have done better if he had just shut up for a few minutes and let me speak. Reverend Grant used the word “bombastic” in describing the approach my opponent used. On the other hand, he also gently pointed out that sometimes this can be how debates are won.

There’s this “On the other hand” tactic in debating and in reflective thought that my debating opponent managed to repeatedly deflect.

I don’t know what ever happened to Reverend Grant. We spoke on the telephone years ago. He sounded much older and a hint of frailty was in his voice.

I could find only a photo on eBay of a man who closely resembles the teacher I knew and the name on the picture is Reverend Hector Grant. The only other artifact is a funeral program for someone I never knew, which lists Reverend Hector Grant as being the pastor and some of the pallbearers were members of one of the Huston-Tillotson College fraternities.

I think it’s unusual for people to disappear like that, especially nowadays when we have the world wide web. Reverend Hector Grant was an important influence for me. He was one of the few black men of professional stature I encountered in my early life.

On the other hand, contrast that with Reverend Glen Bandel, another clergyman who was a white man and another important influence starting in my early childhood. Reverend Bandel persuaded me to be baptized at Christ’s Church in Mason City, Iowa. He radiated mercy, generosity, and kindness. He died in June of this year. I can find out more about him on the web just from his obituary than I can ever find on Reverend Grant, who apparently disappeared from the face of the earth.

Both of these men were leaders for whom skin color didn’t matter when it came to treating others with respect and civility.

My path in life was largely paved by these two clergymen. Reverend Bandel sat up with our family one night when my mother was very sick. His family took me and my little brother into their home when she was in the hospital.

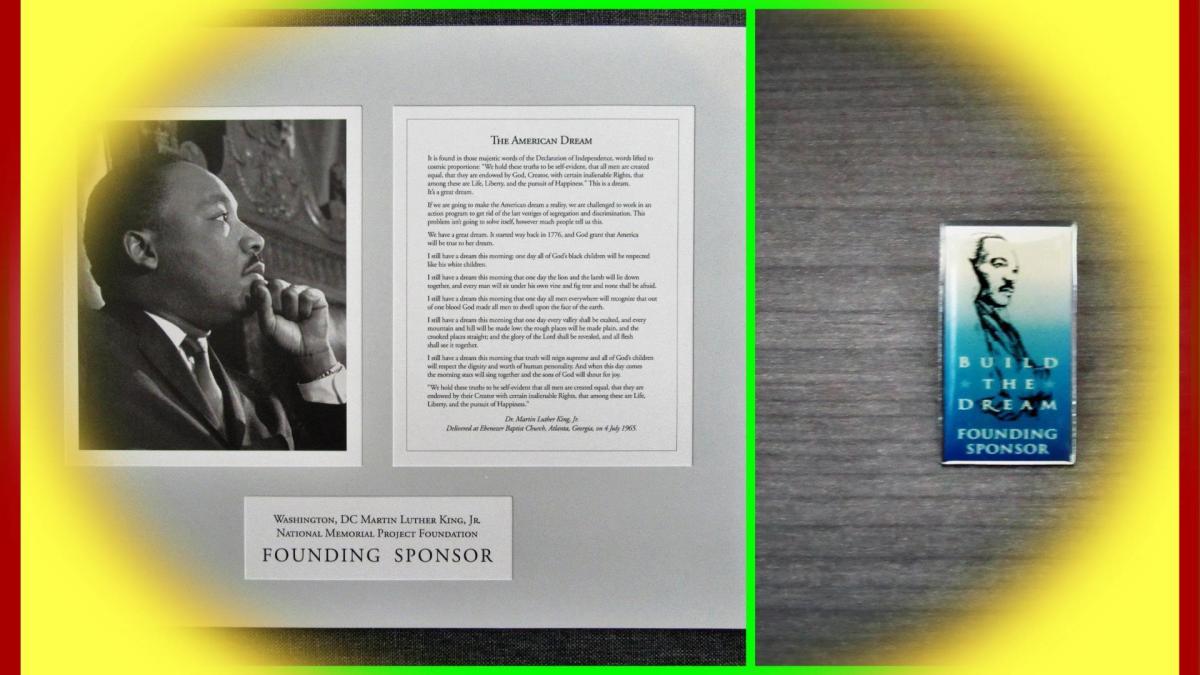

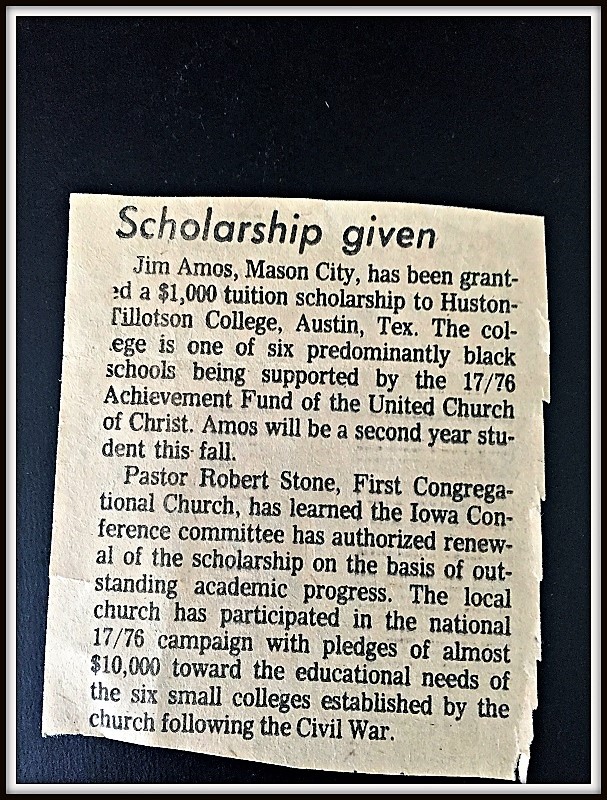

On the other hand, Reverend Grant was instrumental in guiding me to an HBCU where I saw more black people in a couple of years than I ever saw in my entire life. The First Congregational Church in Mason City was instrumental in making that possible because they helped fund the drive to support H-TU (one of six small HBCUs) by the national 17/76 Achievement Fund of the United Church of Christ.

The news is replete with stories, some of them tragic, about how Greek fraternities haze their pledges. On the other hand, H-TU was pretty rough on pledges too. Upper classmen would make the pledges roll down the steep hills around the campus. They looked exhausted, wearing towels around their necks, running in place when they weren’t running somewhere in the Texas heat.

One H-TU professor said that H-TU was “small enough to know you, but big enough to grow you.” Although I can’t remember ever seeing him on campus because he was traveling most of the time, I at least knew the name of the President was John Q. Taylor (1965-1988). On the other hand, when I transferred credit to Iowa State University, I never knew the name of the President of the university.

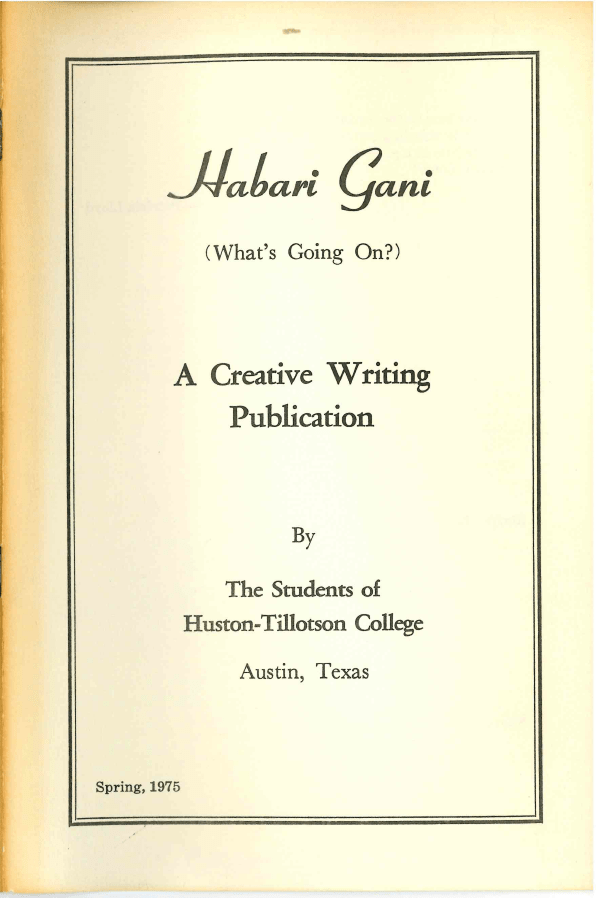

Habari Gani is Swahili for “What’s the news?” or as it translated in the context I’m about to set, “What’s going on?” Habari Gani was the name for the annually published book of poetry by the H-TU students. Dr. Porter supported the project. I submitted a poem for the 1975 edition, which didn’t make the cut. When I transferred to Iowa State University, I left without getting a copy.

On the other hand, years later, I got a digital copy of that edition. I tracked it down to the H-TU library in 2016. The librarian was gracious.

Habari Gani has always been a reminder of the reason why I went to H-TU in the first place. I grew up in Iowa and was always the only black student in school. I grew up in mostly white neighborhoods.

On the other hand, when I finally got to H-TU, one of the students asked me, “Why do you talk so hard?” That referred to my Northern accent, which was not the only cultural factor that made social life challenging.

Once I tried to play a pickup game of basketball in the gymnasium. I’m the clumsiest person for any sport you’ll ever see. I was terrible. But the other players didn’t give me a bad time about it. They softly encouraged me. This was in stark contrast to the time I played a pickup game with all white men years before in Iowa. When I heard one of them yell, “Don’t worry about the nigger!” I just sat down on the bleachers.

On the other hand, when I was a kid and our family was hit by hardship, Reverend Bandel was the kindest person on earth to us—it didn’t matter that he was white. And my 2nd grade teacher, who was black (the only black teacher I ever had before going to H-TU), slapped me in the face so hard it made my ears ring—because I was rambunctious and accidentally bumped into her. It’s far too easy to polarize people as good or bad based on the color of their skin, especially when you’re young and impressionable.

It takes practice and experience to learn how to say and think, “On the other hand….”