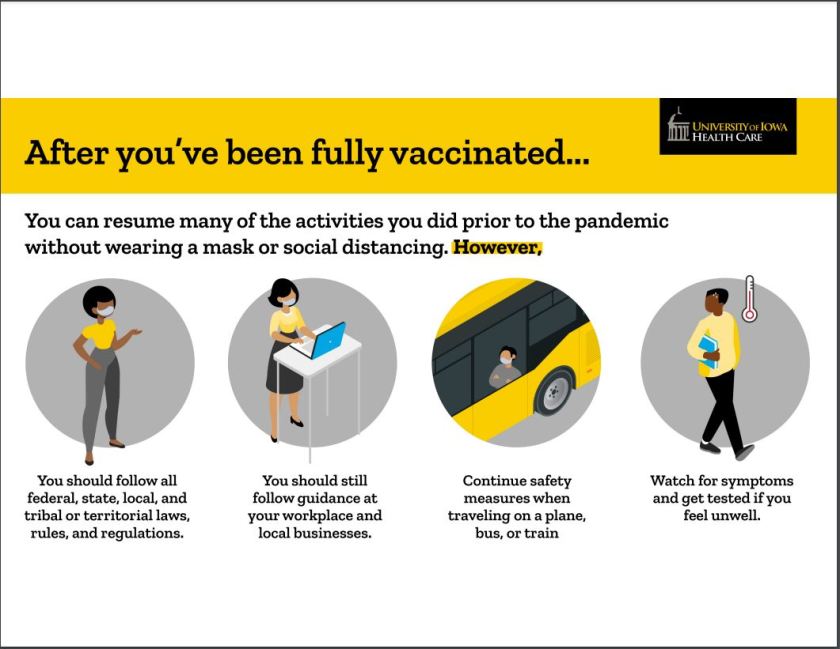

The graphic below is from University of Iowa Health Care. It’s a reminder of what you can do after you’ve been fully vaccinated for COVID-19. You can review CDC guidance here.

We were on our way home yesterday and drove by a couple of restaurants (Wig & Pen Pizza and Vine Tavern and Eatery) with crowded parking lots. We have not seen that since the COVID-19 pandemic hit a year ago. This seemed to coincide with the CDC announcement of the new mask guidance indicating you can ditch the mask both outdoors and indoors—if you’re fully vaccinated. The updated guideline was a little hard to find on the CDC website, I noticed. It didn’t jump right out at you like the update on the pause of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

I checked the websites for both restaurants. They still say you have to wear masks. Pretty soon after that CDC update, news headlines appeared which provoked a few questions. How do you tell the difference between unmasked and masked persons who say they’re fully vaccinated? One headline said something like, “Get vaccinated or keep wearing your mask.”

And I saw a new term today, “vaccine bouncers.” Nobody wants to be a vaccine bouncer. In other words, since you can’t tell by looking at somebody if they’re fully vaccinated, how are you going to confirm the vaccination status of anyone? I don’t think there’s a lot of confidence in the ability to reliably detect the Pinocchio effect. And, regrettably, vaccination cards can be faked.

Some of us are vaccine hesitant. And some of us are unmask hesitant. Even though Sena and I are fully vaccinated, we still tend to wear masks indoors for now. And to be fair, the CDC guidelines stipulate that you should abide by local rules on wearing masks if required by public transportation and stores. But those guidelines are rapidly changing, maybe a little too rapidly for those who paid attention to daily scary news about upticks in coronavirus death rates when people sing too loud.

I feel like telling us to ditch the masks might be another way of offering an incentive to get vaccinated. Most of us hate masks. They’re hot, confining, make us feel too stifled to breathe easily, and so on. On the other hand, getting infected with COVID-19 is the ultimate respiration suppressor. As a recently retired general hospital psychiatric consultant, I’ve been called to critical care units to help manage anxiety in patients bucking respirators, which means they were fighting the ventilator tube. I didn’t have a whole lot to offer.

I think incentives are better than mandates, though (don’t spend it all in one place!). The best incentive is doing something to help all of us recover from the pandemic.

I was watching a TV show about UFOs and aliens the other night when I heard my remote control make clicking noises all by itself. Nothing happened on the set; neither the volume nor the channels changed. This has been happening for months and I usually just ignore it. Maybe it was because of the program I was watching. Get this, hundreds of people witnessed UFOs one night several years ago, even called the local radio station about it—yet no one took a single picture or video.

Before you tell me to adjust the gain on my tin foil hat, let me just say I’ve never seen aliens or UFOs—or Bigfoot. But the night I heard the remote control click away by itself, I got off the couch and searched the internet. It turns out I’m not the only one who has ever experienced this. However, Sena has never heard it.

Obviously, I’m not that anxious about it, but I’m curious. I also found an article on the web about alkaline batteries that pop, hiss, whistle Dixie, etc., especially when they go bad and leak.

I checked the batteries (the remote control takes two alkaline AAs) and noticed they were a brand we’d never bought before Universal Electronics (UEI). They have a website, which didn’t look suspicious. Where did we get them and how did they get into the TV remote control? They don’t have an expiration date on them. They’re made in China, which doesn’t bother me. They looked OK, but I replaced them with Ray-O-Vac batteries yesterday and I’m going to wait and see what happens. Maybe it clicked once on its own last night, but I was napping part of the time and watching Men in Black too. In fact, the remote control is on the table next to me as I’m writing this.

But you know, I can see how this might make other people anxious. This kind of anxiety might fuel the development of conspiracy theories in one person. Somebody else might think about poltergeist activity or interference by aliens practicing interdimensional moon-walking or making you order onion rings when you really want French fries.

It got me thinking about how anxious people can be about getting the COVID-19 vaccine. About a month ago, there were news reports of people having puzzling episodes of fainting, breathlessness, sweating, and other symptoms after getting one of the vaccines. The CDC investigated it and discovered that most of those vaccinated had experienced similar reactions in the past after getting vaccination shots. The upshot of it was they were having anxiety attacks, some of which were in the context of needle phobia.

Shortly after that, I noticed there were more internet articles about needle phobia (trypanophobia) which might be part of the cause of recent vaccine hesitancy. There’s a lot of reassurance and advice out there now about the whole thing. There is even a beer commercial (“your cousin from Boston gets vaccinated”) about a guy fainting when he sees the needle.

I suppose you could try using a Neuralyzer, which was used in all the Men in Black movies. You could flash someone in line for the vaccine who is showing signs of anxiety about getting the shot. The idea is to erase his memory of being needle phobic and replace it with a new one (You love getting vaccines!). You can find a slew of DIY projects on line to make one of your own. Several include 3-D printers, which on average can set you back about $700. You have to know how to use a soldering iron (amongst other skills). I flunked soldering in grade school when I soldered my ear lobe to a tin foil hat, back when they were actually made of tin before the switch to aluminum.

There’s just one problem with Neuralyzers—they don’t actually work. And by the way, tin foil hats can backfire, making it easier for the government to keep tabs on you at certain frequencies. Making tin foil hats is a waste of Reynolds Wrap.

There is some helpful guidance for how to cope with needle phobia, which by the way occurs even in some health care professionals. We’ll get through this somehow. There has not been a peep out of my remote control the whole time I was writing this post.

My wife and I have been immunized against COVID-19 and we recognize that people can be hesitant about getting vaccinated. However, I’m remembering my last few months prior to my retirement a year ago working as a general hospital psychiatric consultant and I saw one or two cases of catatonia in the context of COVID-19 infections.

Catatonia is a complex, potentially lethal neuropsychiatric complication of many medical disorders including COVID-19. It can make a person mute and immobile, often making health care professionals mistake it for primary psychiatric illness (for example, catatonic schizophrenia). You can access a fascinating educational module on the National Neuroscience Curriculum Initiative (NNCI) website about catatonia and how it can be associated with COVID-19.

Catatonia can kill people, rendering them unable to move or eat, leading to blood clots and dehydration among a host of other complications. You’ve seen the news stories about blood clots being an extremely rare but deadly side effect of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine. The risk for blood clots is actually higher from COVID-19 infection itself compared with the very low risk from the vaccine.

I made a YouTube video about catatonia and other neuropsychiatric emergencies and that presentation continues to be viewed fairly often. You’ll want to crank up the volume.

I wrote a blog post about catatonia in the setting of delirium a couple of years ago and the information in it is still relevant below.

Catatonic patients may have a fever and muscular rigidity that leads to the release of an enzyme associated with muscle tissue breakdown called creatine kinase (CK). The level of CK can be elevated and detectable on a lab test.

Many patients will have a fast heart rate and fluctuating blood pressure. They may sweat profusely which can lead to a sort of greasy facial appearance. They may have a reduced eye blink rate or seem not to blink at all. They may display facial grimacing.

The patient may exhibit the “psychological pillow” (some call this the “pillow sign”). While lying in bed, the patient holds his head off the pillow with the neck flexed at what looks like an extremely uncomfortable angle. The position, like other odd, awkward postures can be held for hours.

Catatonia can be caused by both psychiatric and medical disorders. It tends to be more common in bipolar disorder than in schizophrenia even though catatonia has historically been associated with schizophrenia as a subtype. You can also see it in encephalitis, liver failure, and in some forms of epilepsy and other medical conditions—to which we can now add COVID-19 infection.

The patient may perseverate or repeat certain words no matter what questions you ask. He may simply echo what you say to him and that’s called “echolalia”.

Although catatonic stupor is what you usually see, less commonly you can see catatonic excitement, which is constant or intermittent purposeless motor activity.

The usual way to assess catatonic stupor in order to distinguish it from hypoactive delirium is to administer Lorazepam intravenously, usually 1 to 2 milligrams. A positive test for catatonic stupor is a quick and sometimes miraculous awakening as the patient returns to more normal animation. The reaction is usually not sustained and the treatment of choice is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), which can be life-saving because the consequence of untreated catatonia can be death due to such causes as dehydration and pulmonary emboli.

Another less invasive test that doesn’t use medicine is the “telephone effect” described in the 1980s by a neurologist, C. Miller Fisher. It was used to temporarily reverse abulia or akinetic mutism, which in a subset of cases of stupor are probably the neurologist’s terms for catatonia. Sometimes the mute patient suffering from abulia can be tricked into talking by calling him on the telephone. It’s pretty impressive when a patient who is mute in person answers questions by simply calling him up on the telephone just outside his hospital room.

So that, in my opinion, is yet another reason to get the COVID-19 vaccine.