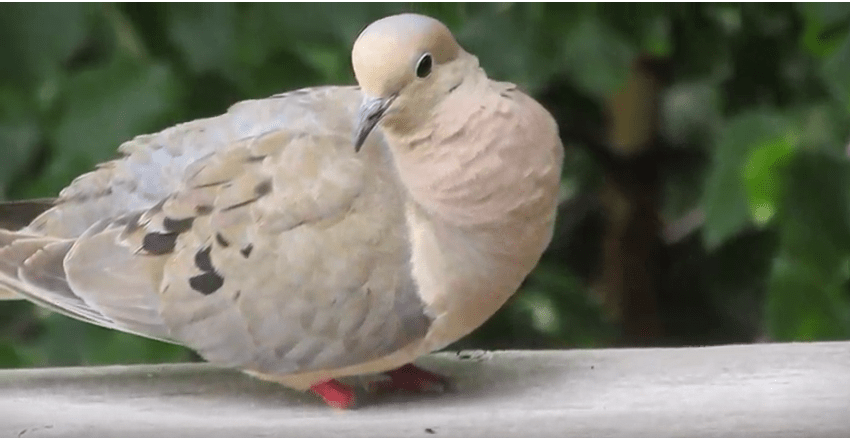

I recently got my first and only comment on a blog post I posted on March 30, 2019 about toeless mourning doves which were visiting our backyard deck of a house in which we lived previously. I also found an article published about the issue later that year in December of 2019, which is about pigeons losing toes. Pigeons and mourning doves are not exactly the same (although they are relatives within the same family), but apparently pigeons are thought by the authors of the article to lose their toes because of urban pollution.

The commenter is from West Texas who has seen toe deformities, notes that it’s a new problem to him (never saw it prior to this year), remarks that the toe deformities were visible in newly hatched birds and further suspects the problem is more complicated than exposure to stringfeet or frostbite injury.

When I searched the web for more information, what appeared is my 2019 blog post at or near the top of the page and little else. There was one news item about the issue published in 2021 suggesting the problem of missing toes in doves at that time was probably due to frostbite from a winter storm in North Texas.

We haven’t seen any mourning doves lately. They don’t frequent our new property, which is actually close to the same neighborhood where we observed the toeless birds several years ago.

So, the mystery deepens. If anyone has new information, let me know.

New reference:

Frédéric Jiguet, Linda Sunnen, Anne-Caroline Prévot, Karine Princé,

Urban pigeons losing toes due to human activities,

Biological Conservation,

Volume 240,

2019,

108241,

ISSN 0006-3207,

(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006320719306901)

Abstract: Measuring the impacts of urban pollution on biodiversity is important to identify potential adaptations and mitigations needed for preserving wildlife even in city centers. Foot deformities are ubiquitous in urban pigeons. The reasons for these mutilations have been debated, as caused by frequenting a highly zoonotic environment, by chemical or mechanistic pigeon deterrents, or by necrosis following stringfeet. The latter would mean that pigeons frequenting pavements with more strings and hairs would be more exposed so subject to mutilations. We tested these hypotheses in Paris city (France), by recording the occurrence and extent of toe mutilations on samples of urban pigeons at 46 sites. We hypothesized that mutilations would be predicted by local overall environmental conditions, potentially related to local organic, noise or air pollutions, so gathered such environmental predictors of urban pollutions. We showed that mutilations do not concern recently fledged pigeons, and that their occurrence and frequency are not related to plumage darkness, a proxy of a pigeon’s sensitivity to infectious diseases. Toe mutilation was more frequent in city blocks with a higher degree of air and noise pollution, while it tended to increase with the density of hairdressers. In addition, the number of mutilation on injured pigeons was higher in more populated blocks, and tended to decrease with increasing greenspace density, and to increase with air pollution. Pollution and land cover changes thus seem to impact pigeon health through toe deformities, and increasing green spaces might benefit bird health in cities.

One sentence summary

Toe mutilation in urban pigeons is linked to human-induced pollution.

Keywords: Columba livia; Feral pigeon; Toe mutilation; Stringfeet; Urban pollution